Domestic Outmigration From Some Urban Counties Slowed, Smaller Gains in Rural Counties

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the U.S. population in many ways, including births, deaths and international migration. One of its more intriguing impacts was on domestic migration patterns.

Some longstanding trends accelerated, such as outmigration from large urban areas in the Northeast, while other trends reversed, resulting in some small rural counties gaining rather than losing population.

Today’s release of Vintage 2022 population estimates provides a snapshot of changes in domestic migration during the first years of the pandemic.

In the wake of the pandemic’s remarkable impact on domestic migration, parts of the country began showing signs of a rebound.

Note that we include the change in the nation’s group quarters (GQ) population in the estimates’ net domestic migration component. But we excluded it from this analysis (due to the volatility of this population during the pandemic) to focus only on household population movement.

Migration Pre-Pandemic

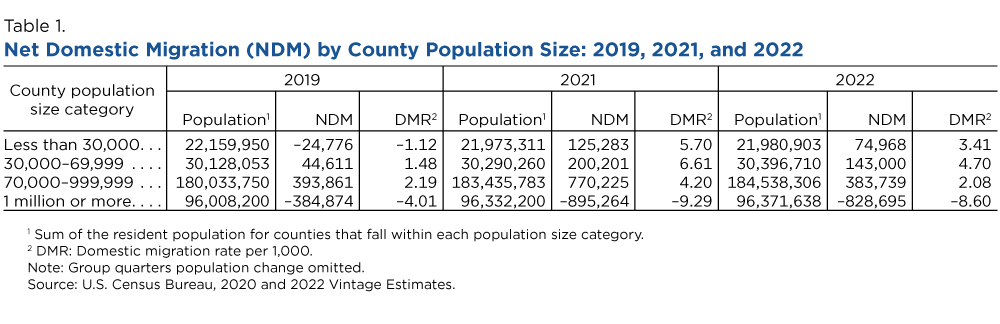

In 2019, the year before the pandemic hit the United States, smaller counties with fewer than 30,000 people lost population through net domestic migration.

During the pandemic’s peak, between 2020 and 2021, this flipped, and these least populous counties gained people through domestic migration.

In 2022, they experienced smaller population bumps from domestic migration.

At the other end of the spectrum, the largest counties with populations of 1 million or more were losing people through domestic migration before the pandemic. But the pandemic exacerbated this outmigration substantially and in the last year, this domestic outmigration diminished somewhat in certain regions.

In the wake of the pandemic’s remarkable impact on domestic migration, parts of the country began showing signs of a rebound:

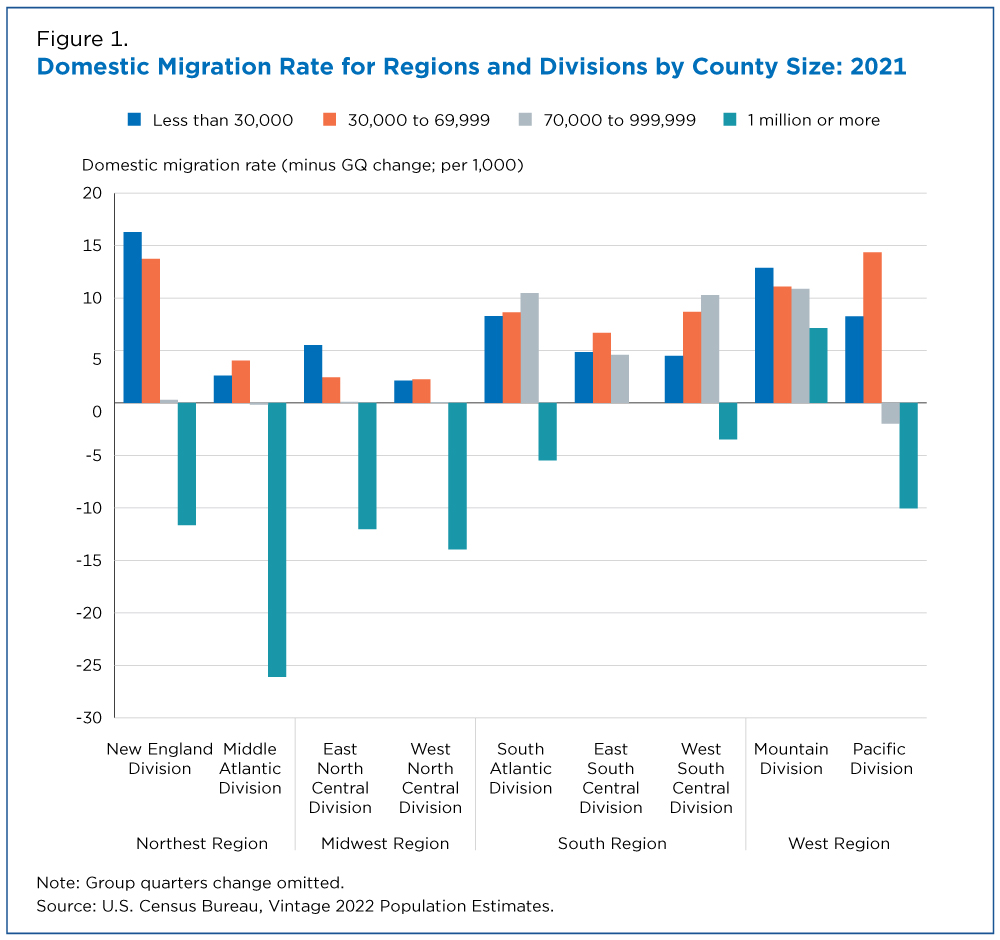

- Populous areas in the South and West, where growth through domestic migration waned at the height of the pandemic, resumed their pre-pandemic patterns. For example in Texas, Dallas County had net domestic outmigration of 25,000 in 2019 and 43,000 in 2021. The loss narrowed to just over 20,000 in 2022.

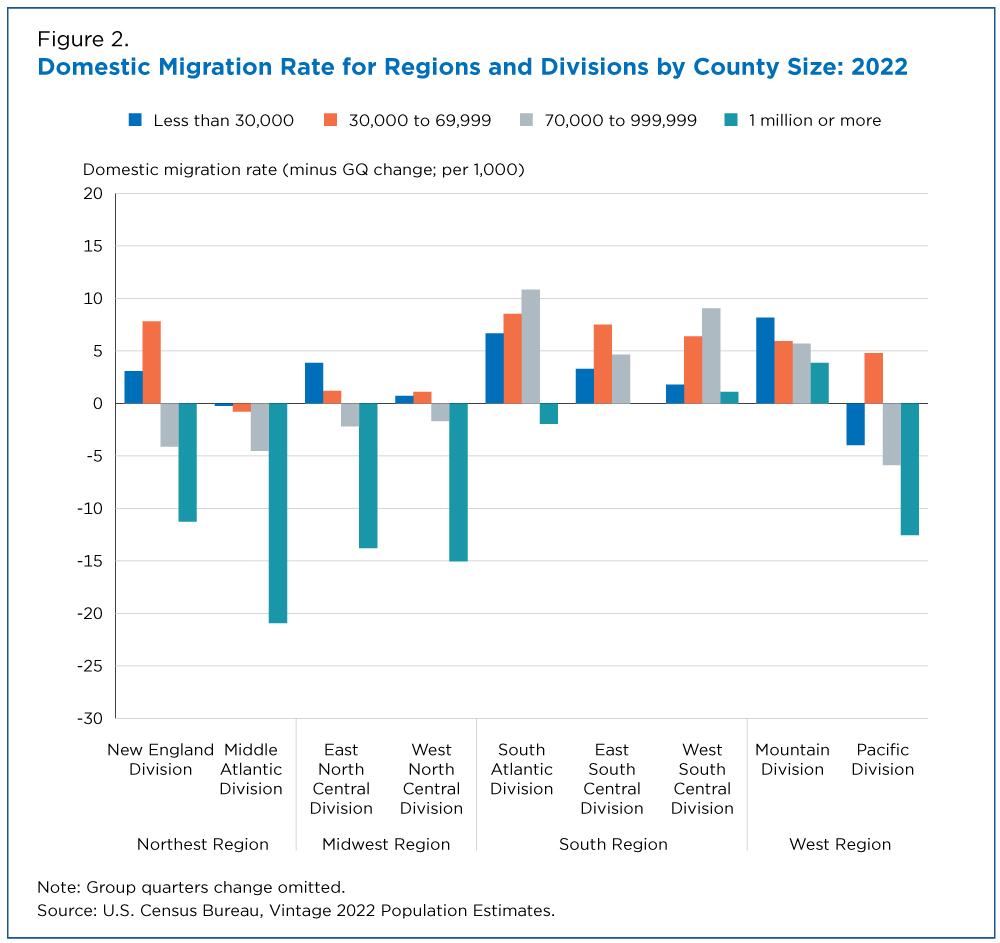

- Some major metro areas in the Northeast and Midwest that experienced a temporary lessening of net domestic outmigration during the peak pandemic had an increase in 2022.

- In New England, mid-sized counties with a population between 70,000 and 999,999 saw a very slim gain from net domestic migration in 2022.

- In the Middle Atlantic, small counties (under 70,000 population) saw gains from net domestic migration in 2022.

- In the Pacific Division, the smallest counties (under 30,000 population) saw a notable gain from domestic migration between 2020 and 2021. Most of the largest counties (over 1 million population) showed substantial losses that year. In many cases, these losses were higher than in prior years.

Fast Forward to 2021-2022

On average, small counties that saw growth in net domestic migration the first year of the pandemic returned to pre-pandemic levels of slow or declining net domestic migration from 2021 to 2022.

The same reversal happened in the largest counties — losses they had experienced the previous year slowed:

- In the West South Central Division (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas), a net loss of domestic migrants between 2020 and 2021 transitioned into a net gain between 2021 and 2022.

- In the West’s Mountain Division (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming) a net gain of domestic migrants slowed slightly.

Visualizing the Patterns

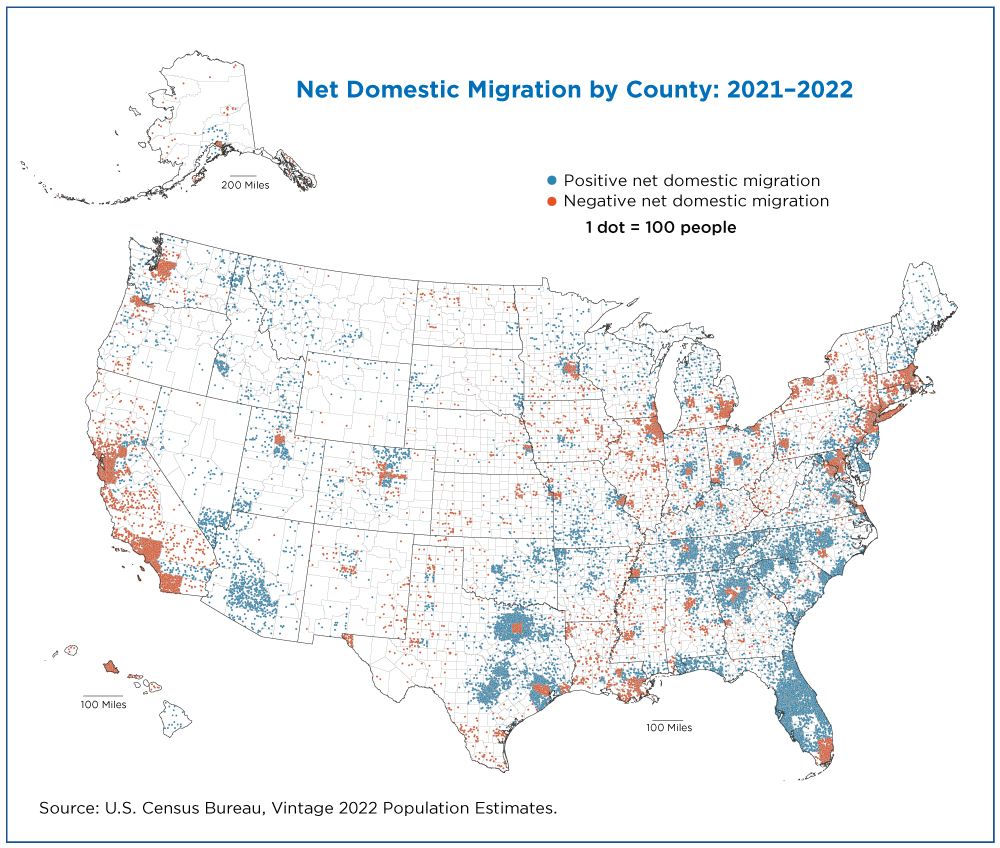

These patterns are more evident in the accompanying dot-density map for 2022, where each green dot represents a net gain of 100 domestic migrants and a red dot represents a net loss of 100 domestic migrants.

In the northeast corridor, particularly around Washington, D.C., New York, and Boston, there are pockets of red — these are generally urban areas that traditionally experience net domestic outmigration.

In Florida, the Miami area is a distinct pocket of net domestic migration loss in the heart of a state with mostly net domestic migration gains.

Other noteworthy places with large net domestic migration losses were upstate New York and the larger metro areas along the Great Lakes. Additionally, the major metro areas on the West Coast, from San Francisco to Los Angeles to San Diego, had substantial net domestic outmigration.

In the Pacific Northwest, Portland and Seattle also stand out for net domestic migration losses.

While parts of the United States lost population through net domestic migration, this also means other parts gained.

The gainers are shown in green on the map. Most areas with large net domestic migration gains were in the South or West.

Fast-growing metro areas in the West, such as Las Vegas and Phoenix, showed notable growth. In the South, net domestic migration gains were seen in Florida, the Carolinas, north Georgia (surrounding Atlanta), and in the major metro areas of Texas — although not in the urban cores of Dallas or Houston.

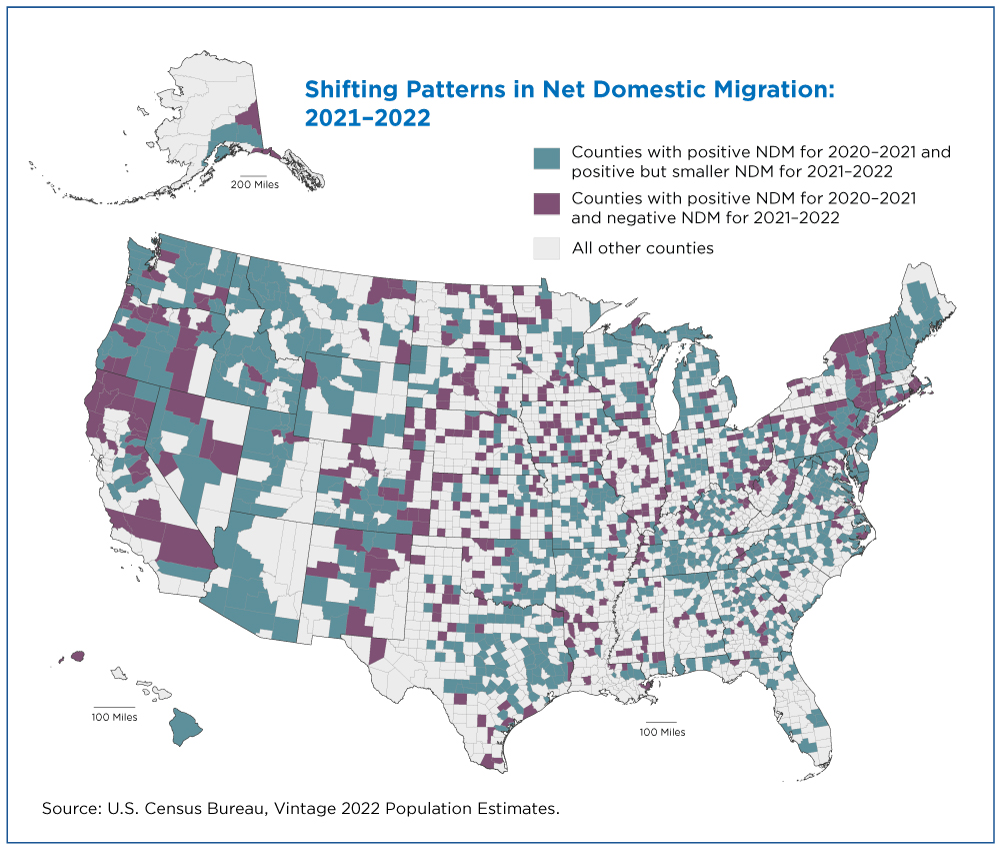

While it’s informative to see the broad patterns of domestic migration in 2022, the changes in net domestic migration (NDM) from the prior year are striking.

The map below shows counties that grew both years but saw their growth diminish (green). It also shows counties that grew between 2020 and 2021 but shrunk between 2021 and 2022 (red).

In addition, many rural areas that gained domestic migrants during the pandemic, saw those gains slow or reverse completely.

Another interesting pattern is how some places with natural amenities, like those along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan, experienced growth in 2021, which then slowed in 2022.

As the decade continues, the Census Bureau’s annual population estimates will show if these new patterns of net domestic migration were short-lived or will become more enduring trends.

Related Statistics

Stats for Stories

Press Kit

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.