White Women More Likely Than Black Women to Move Up Income Ladder Due to Differences in Partnering, Men’s Incomes

White women were not only more likely than Black women to have a spouse or partner but their spouses and partners tended to earn more, making White women more likely to attain upward mobility through partnerships, according to new U.S. Census Bureau research.

White women who grew up in families in the bottom 20% income bracket were more likely than Black women from the same economic background to move out of the bottom bracket up to the top 20% income bracket.

No matter their childhood family income, White and Asian women were more likely than women from other race/ethnic groups to have access to more income as adults because they were more likely to have a partner and that partner was more likely to be affluent.

But this wasn’t because of differences in personal income since Black and White women from similar economic backgrounds had similar personal incomes.

It was because White women had access to more income from spouses and unmarried partners, according to the study exploring how marriage and partnerships affect a woman’s chances of being better off economically than their parents.

Measuring Family Income in Adulthood and Childhood

Researchers analyzed a sample of adults who responded to the American Community Survey (ACS) between 2011 and 2019. The sample included women ages 28 to 32 and men ages 31 to 35 (since women tend to partner with slightly older men).

They focused on Black and White women but also examined some outcomes for women and men from other racial and ethnic groups.

The study classified people as Black, White, Asian or American Indian/Alaska Native if they identified as that race only and did not identify as Hispanic. It classified people as Hispanic if they identified as Hispanic, regardless of their race.

A person’s adulthood family income is their personal income and, if they live with a spouse or unmarried partner, the income of their partner. (Due to data limitations, this analysis was limited to different-sex couples.)

A person’s childhood family income is the average income of their parents or the adults who supported them when they were between the ages of 10 and 18. The ACS does not collect this information, so the study linked respondents’ survey records to federal income tax records of the people who claimed them as dependents when they were children.

Partnering by Race, Ethnicity and Childhood Family Income

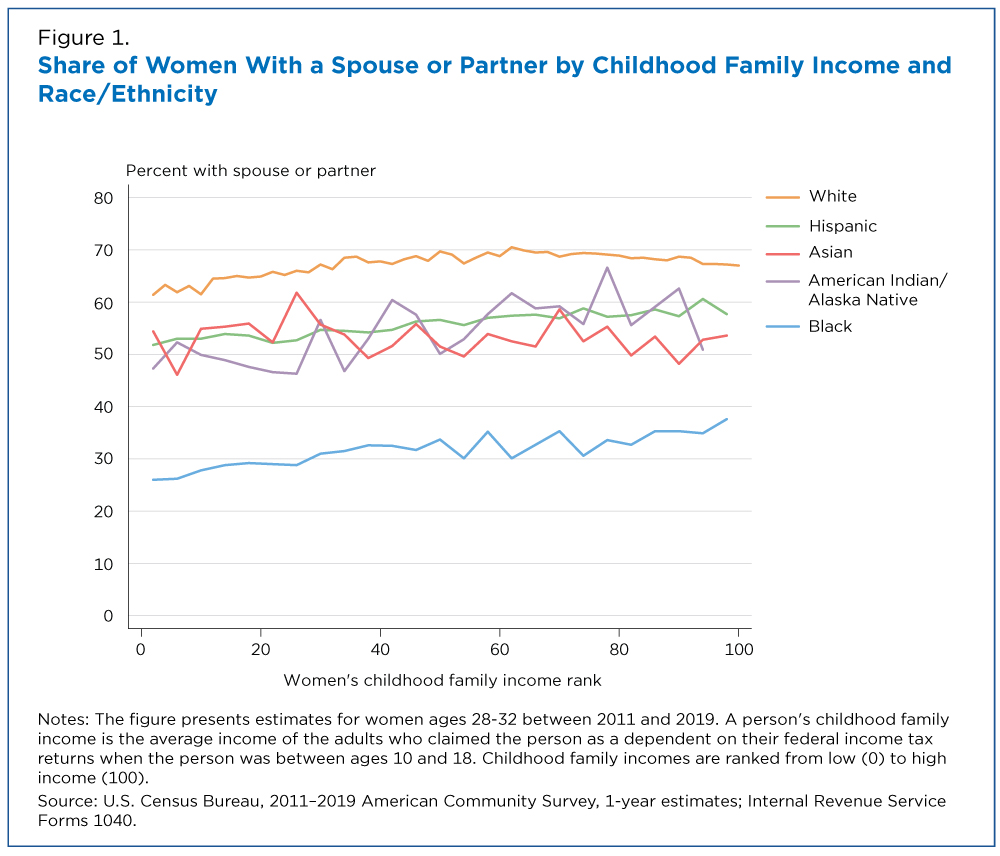

Figure 1 shows that White women are more likely than women from other race and ethnic groups to live with a spouse or unmarried partner, regardless of their economic background.

Among women from the middle of the childhood family income distribution, nearly 70% of White women were partnered, compared to 34% of Black women and between 50% and 60% of Hispanic, Asian and Native American/Alaska Native women.

These differences in partnering rates also hold for women who grew up in lower- and upper-income families. At each point in the childhood family income spectrum, White women were at least 75% more likely than Black women from the same economic background to be partnered.

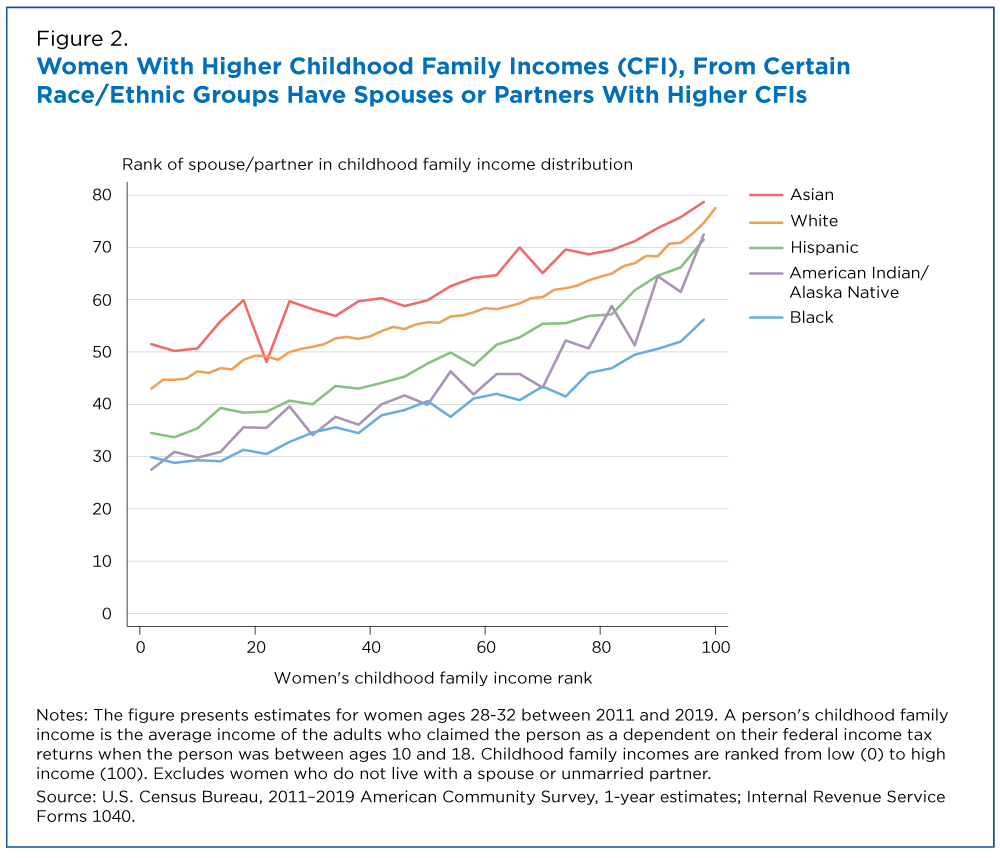

Figure 2 shows that, among women with a spouse or unmarried partner, the economic background of the partner depended on both the woman’s race/ethnicity and economic background:

- Among women in each race and ethnic group, those with higher childhood family incomes tended to have partners with higher childhood family incomes.

- Among women in each childhood family income bracket, White and Asian women tended to have partners with higher childhood family incomes than Black, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska Native women.

- When taking women’s race, ethnicity and economic background into account, a Black woman had to come from a much more affluent family to expect as much partner income as a White woman.

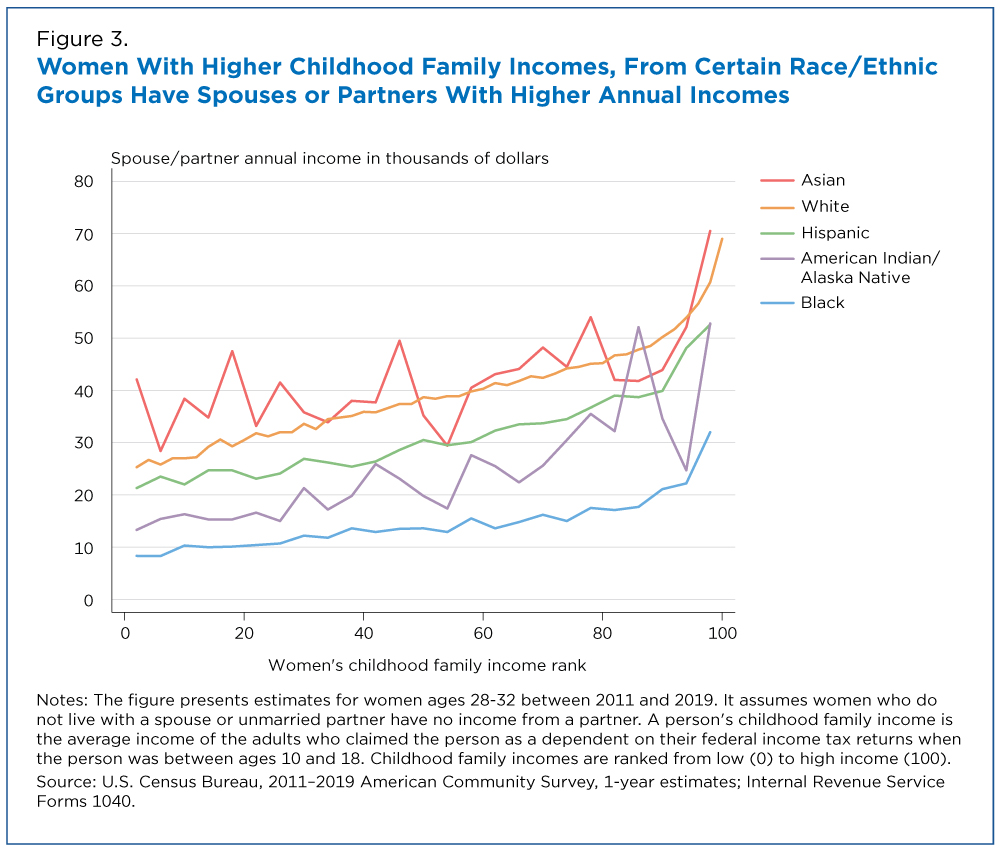

No matter their childhood family income, White and Asian women were more likely than women from other race/ethnic groups to have access to more income as adults because they were more likely to have a partner and that partner was more likely to be affluent.

For example, Figure 3 shows that a White woman who grew up in the bottom 10% of family income bracket could expect partner income similar to that of a Black woman who grew up in the top 10% of family incomes.

Income from Partners Boosts Upward Mobility

The study included a simulation to show how altering women’s personal incomes or their partners’ incomes would affect their chances of being economically better off as adults than as children.

The simulation showed that giving women from less-advantaged race/ethnic groups similar personal incomes as White women did little to improve their chances of upward mobility. The exception was American Indian/Alaska Native women, whose probability of moving out of the bottom 20% family income level increased by 9 percentage points.

In contrast, pairing women from less-advantaged race/ethic groups with similar-earning partners as White women improved their chances of moving up.

The improvement was most pronounced for Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women, whose probability of moving out of the bottom 20% family income bracket increased by 15 and 12 percentage points.

Community Inequality, Segregation Increase Gaps in Upward Mobility

To understand how community conditions affect women’s chances at upward mobility, researchers compared Black and White women born in communities with different levels of income inequality and race-based residential segregation.

They defined a community as a core-based statistical area (CBSA), a group of one or more counties that share an urban center and are economically linked through commuting patterns.

Community-level income inequality hindered upward mobility more for Black than White women. In a typical community, the average person who grew up in the top 20% of family incomes was four times better off than the average person who grew up in the remaining 80%. Increasing the level of income inequality reduced the income Black women could expect from a partner.

Racial segregation also contributes to the racial gap in upward mobility. In a typical community, between 50% and 60% of residents would need to change neighborhoods to equalize the racial composition of all neighborhoods in the community.

Related Statistics

-

Stats for StoriesNational Spouses Day: January 26, 2024According to the Current Population Survey 2023 ASEC Supplement, there are some 133.1M married adults age 15+ in the U.S., not counting 4.6M who are separated.

-

Stats for StoriesUnmarried and Single Americans Week: September 17-23, 2023In 2022, about 132.3 million or 49.3% of Americans age 15 and over were unmarried, according to the Current Population Survey.

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.

-

America Counts StoryMarriage Prevalence for Black Adults Varies by StateJuly 19, 2022While the United States as a whole saw a 1.9 percentage-point decrease in married Black adults, four states experienced a significant increase.

-

America Counts StoryMarital Histories Differ Between Native-Born and Foreign-Born AdultsMay 03, 2021New Census Bureau report reveals foreign-born people are more likely than native-born to marry, are older when they first marry and are less likely to remarry.

-

America Counts StoryMoney, Marriage and MillennialsJune 26, 2018A new study finds that jobs, wages, poverty and housing all relate to marriage rates for young adult men and women.

-

Business and EconomyExploring New Frontiers With the Quarterly Workforce IndicatorsJanuary 13, 2026New data on employment and hiring for detailed national industries enable data users to explore the composition and dynamics of specialized workforces.

-

Business and EconomyEconomic Census Highlights Variety of Products Many Industries SellJanuary 06, 2026North American Product Classification System (NAPCS) Data Release from the 2022 Economic Census is a treasure trove of unique information.

-

Business and EconomyRevenue and Employment Trends Reveal Shifts in U.S. EconomyDecember 30, 2025Revenue and employment losses in select retail industries continued, while online sales brokers and local delivery boomed.

-

EmploymentThe Stories Behind Census Numbers in 2025December 22, 2025A year-end review of America Counts stories on everything from families and housing to business and income.