Nepal: Population Vulnerability and Resilience Profile

Nepal: Population Vulnerability and Resilience Profile

Summary

Demography

When compared to the rest of the world, the population of Nepal is growing near the global rate, has fertility below replacement level (total fertility rate of 1.9), high emigration (net migration rate of –4.2 in 2022), lower levels of urbanization (21 percent in 2022), and lower levels of education (5.1 mean years of schooling in 2021).1 Low fertility and high emigration lead to a faster pace of population aging. Substantial disparities are observable between genders, among provinces, and between urban and rural areas.

Economy

Nepal is a lower middle-income country. Its population is mostly rural (79 percent in 2020) and engaged in agriculture (66 percent), which produces one-third of the national gross domestic product (GDP). High emigration contributes significantly to the national economy with personal remittances representing almost one-fourth of the GDP. There are substantial urban and rural differences and variation between regions.

Infrastructure

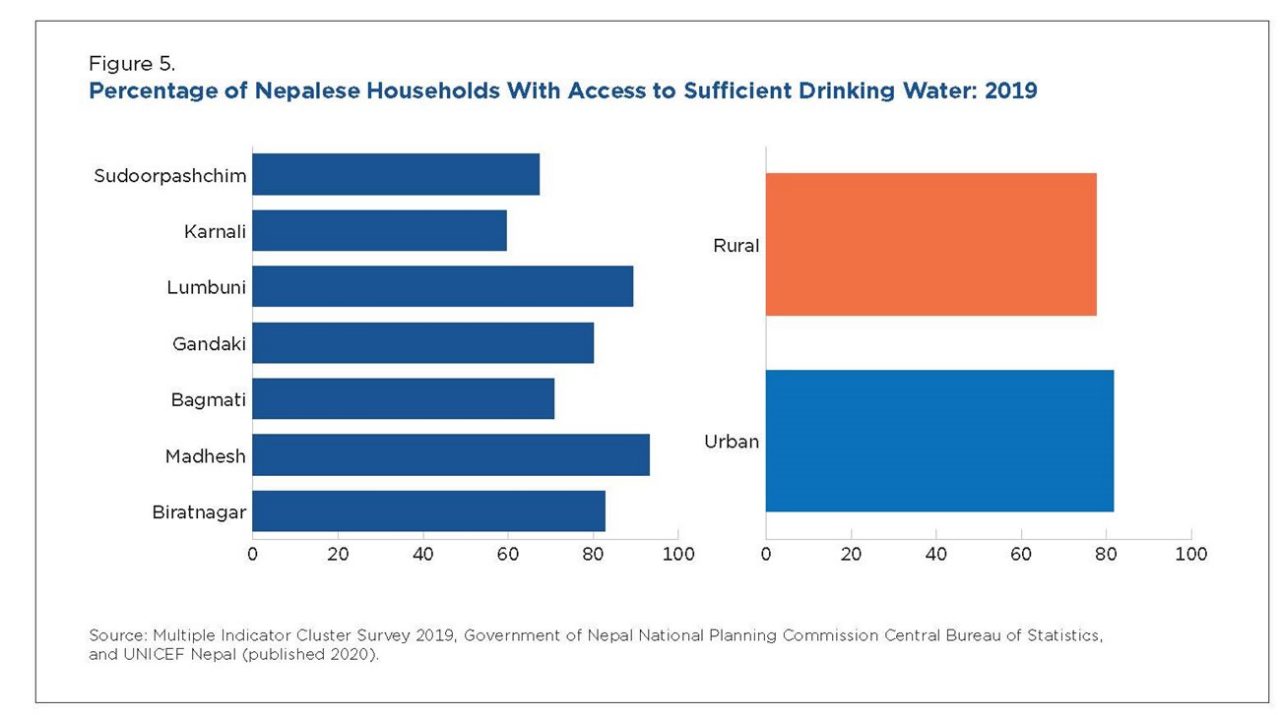

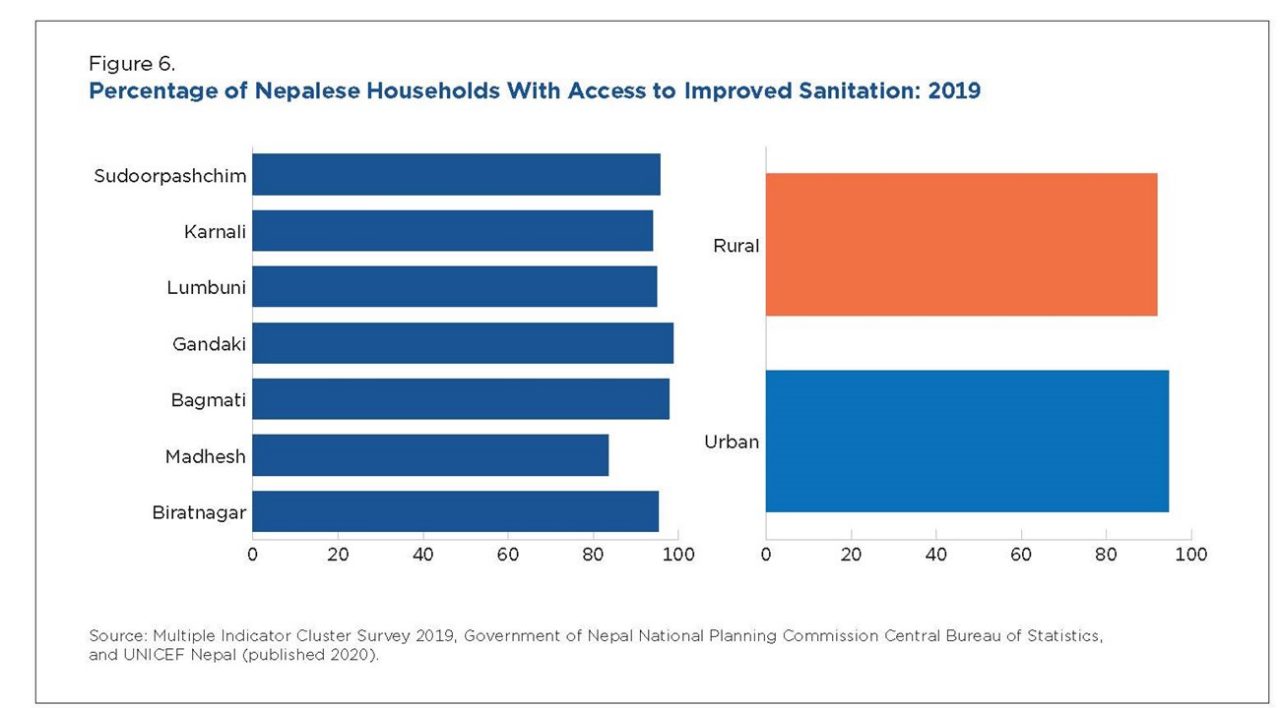

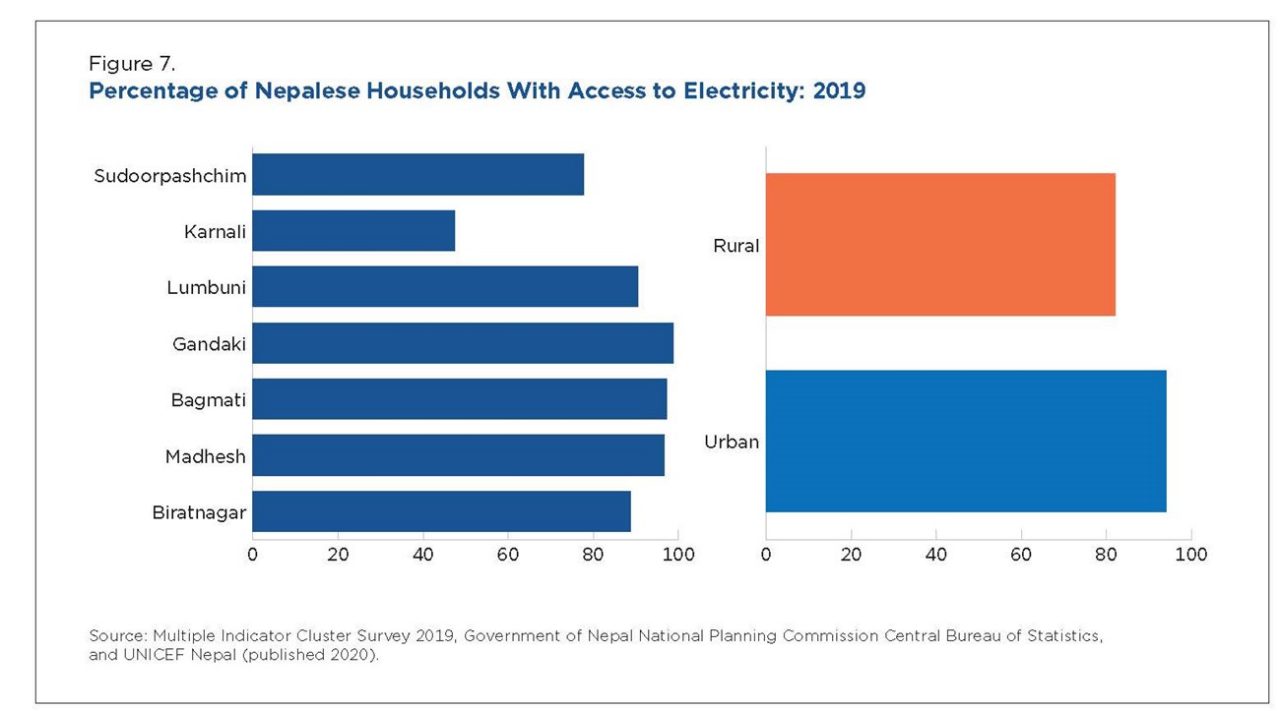

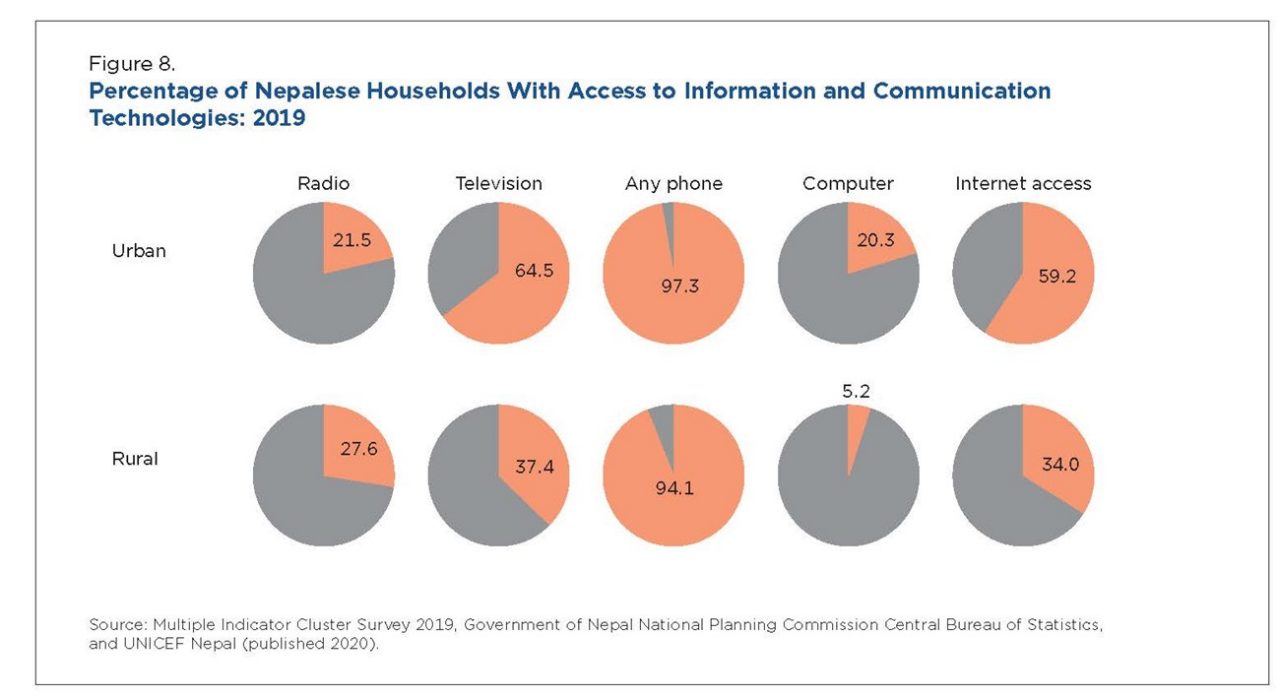

More than 90 percent of the Nepali population has access to phones and improved sanitation. Access to sufficient clean water and electricity is also high (over 80 percent). There are substantial differences between urban and rural areas for access to television, computers, and the internet.

Environment

Soil erosion and deforestation are increasing in Nepal. Climate change is expected to bring more intense rainfall and hot days that will precipitate an increase in the levels of precipitation and number of extreme events in the mid-hills area (until 2050). Other areas—such as the Seti Khola catchment in the western part of the country—are projected to see a decrease in precipitation. Increases in temperature are expected to result in a 16 percent increase in rice production in the colder hills and mountains by 2080.

Demographic Dimension

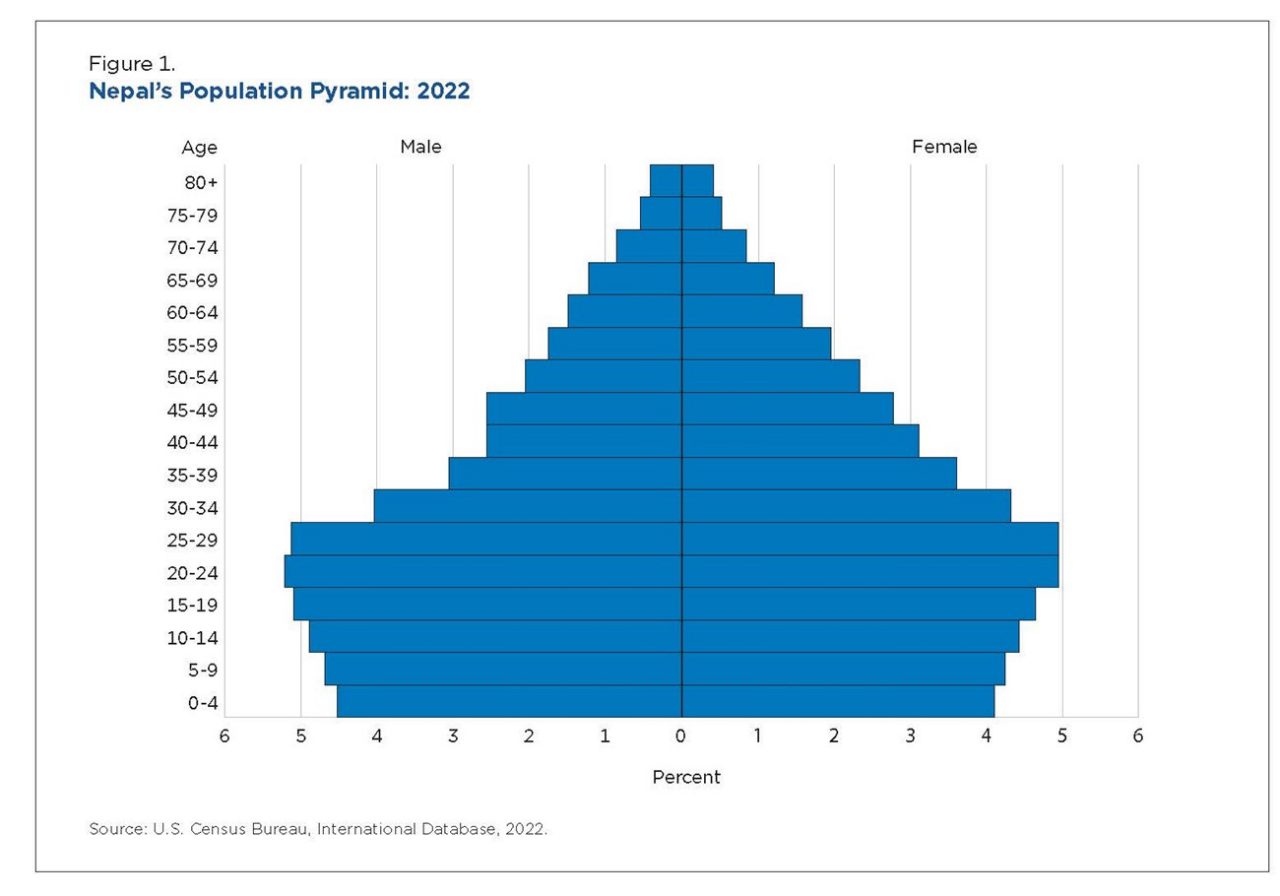

A landlocked rural country in South Asia (urbanization rate 21 percent in 2021), Nepal has 753 municipalities and villages grouped into districts that form seven regions.2,3 It has a population of 30.7 million and population density of 213.9 persons per square kilometer, lower than the average in Southern Asia (313.8 persons per sq. km.).4 Nepal has a relatively young population (Figure 1), with 46.7 percent aged 24 and below.5 The percentage of rural population (79 percent) is also higher compared to other countries in South Asia (65 percent) as of 2020.6,7

Its population increased by 30.6 percent between 2000 and 2022 (from 23,486,982 to 30,666,598), with an annual growth rate of 0.8 percent in 2022. The total fertility rate was estimated to be 1.9 in 2022 (below replacement level), while the net migration rate is –4.2 percent.8

The significant drop in fertility during the past 20 years and the relatively small percentage of older adults (6.0 percent aged 65 and over in 2022) leads to a low dependency ratio (48.9 percent) that is projected to decrease further to 44.6 percent by 2050. A low dependency ratio is a potential resiliency factor when a society is confronted with natural disasters or financial distress.

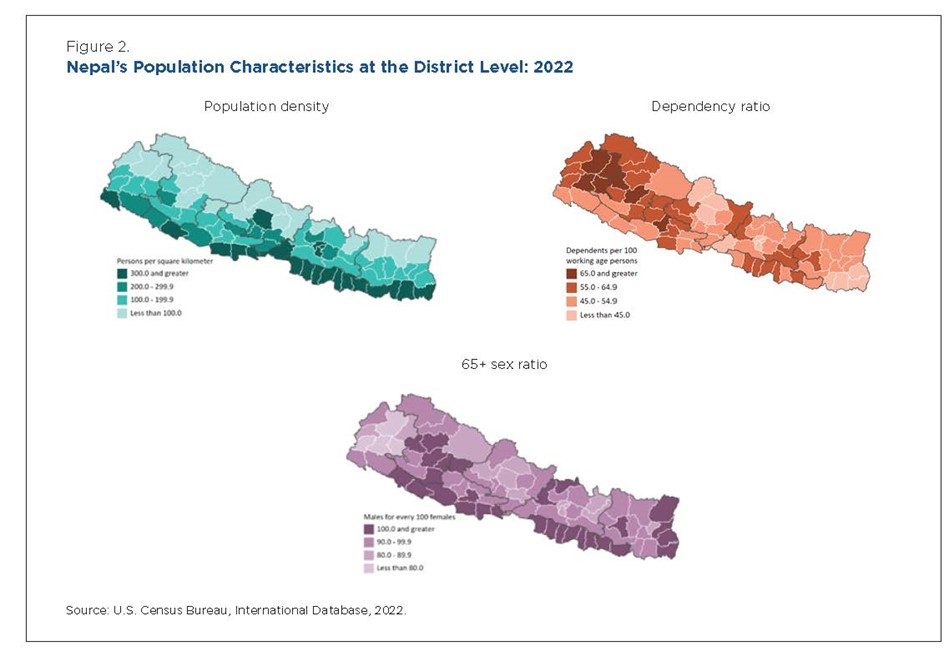

At the subnational level, western Nepal has a higher population density while eastern Nepal—mostly mountainous—has the lowest density, below 100 people per square kilometer (Figure 2). Very few local areas have a dependency ratio above 65 percent, which probably relates to a higher rate of emigration.

In 2022, the life expectancy was 72.4 years, reflecting a substantial improvement from 41.9 years in 1972. Similarly, Nepal has made notable strides in reducing the child mortality rate (under the age of 5) from 256.7 in 1972 to 31.1 in 2022.9

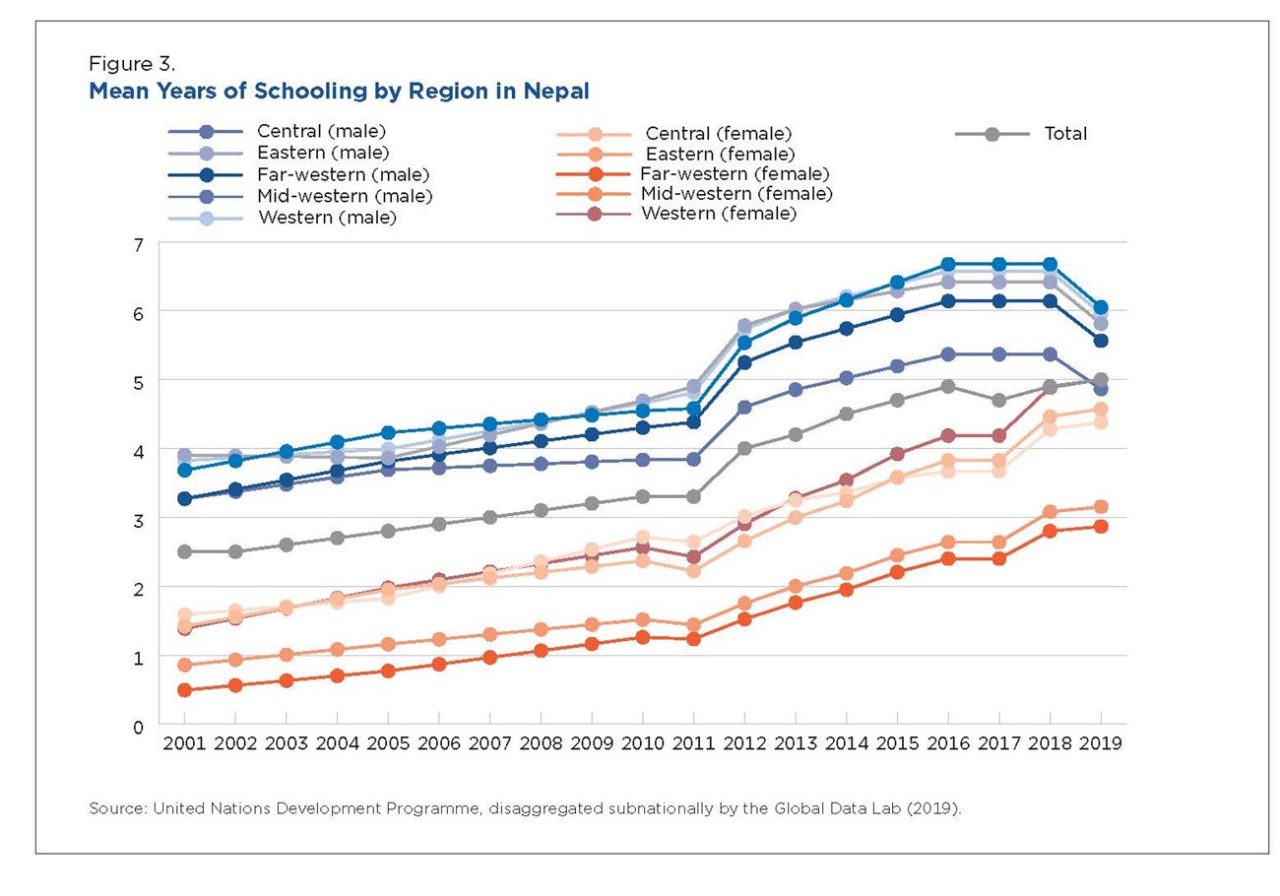

Nepal has a low Human Development Index, ranked 143 out of 191 countries in 2021, and a low level of education (5.1 years of schooling in 2021).10 Although the mean years of schooling has increased for all regions of Nepal since 2002 (Figure 3), it remains low, at about one-half of the global median.11 For all regions, there are large gender differences, with men having about twice the mean number of years of schooling as women. Men from the Central, Eastern, and Western regions are the most educated, with 6 and more years of schooling on average (6.4–6.7 years), while the most educated women are in the Western region with 4.9 mean years of education in 2018 (Figure 3).

In terms of food security, Nepal ranked 74 out of 113 countries in the Global Food Security Index in 2022, with its lowest score recorded on the sustainability and adaptation dimension.12 Based on the 2016 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 51.8 percent of households were food insecure in 2016. Rural areas had a higher percentage of food insecure households (61.2 percent) than the national average; among provinces, Karnali (Province 6) had the highest (77.5 percent) and Gandaki (Province 4) the lowest (44.0 percent) level of food insecurity.

Economic Dimension

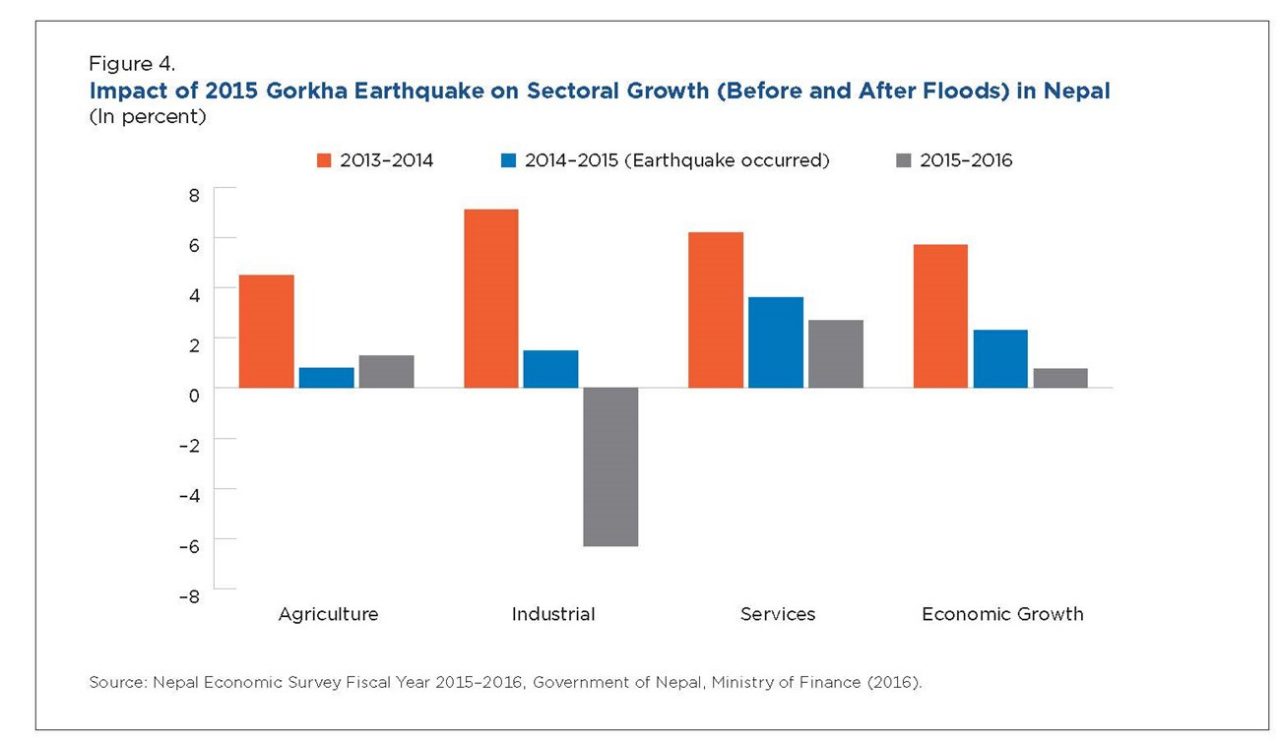

Nepal is classified by the World Bank as a lower middle-income country, with a GDP purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita of $3,996.7 in 2020.13 Although Nepal has been successful in decreasing poverty levels and income inequality, it has a slow rate of economic growth and it remains one of the poorest countries in Asia.14 Its GDP per capita rate of growth is less than one-half of the average in South Asia (2.4 percent versus 7.1 percent for South Asia in 2021), as its topography and frequent natural disasters negatively influence its economic growth.15 In 2015, for example, two earthquakes (with magnitudes of 7.8 and 7.3, respectively) affected Nepal, killing almost 9,000 people and injuring another 100,000. Over one-half million houses were destroyed and another 269,000 were damaged, negatively affecting multiple sectors of the economy and the overall rate of economic growth (Figure 4).16

The incidence of poverty decreased from 30.1 percent in 2014 to 17.4 percent in 2019, but rural areas have the highest concentration of poverty. While 12.3 percent of urban dwellers are poor, 28 percent of those living in rural areas live in poverty.17 About one-third of the country’s GDP comes from agriculture and 66 percent of its people are engaged in farming.18 Low per capita arable land availability (0.082 hectares per person, less than one-half of the world average), low productivity, as well as land fragmentation and degradation make it difficult to increase the financial returns from agriculture.18

Remittances received from migration represent 24.3 percent of the Nepali GDP and are one of the most important contributors to poverty reduction.20,21 However, a high level of emigration also increases the rate of population aging in the country.

Infrastructure Dimension

Clean Water and Sanitation

In Nepal, 81.6 percent of households in urban areas and 77.7 percent in rural areas have access to sufficient drinking water when needed.22 More than 90 percent have access to improved sanitation (Figure 5).

Electrical Grid

There is widespread access to electricity, with 82.2 percent of rural and 94.4 percent of urban households having access. The province of Karnali stands out because less than 50 percent of its households (47.4 percent) have access to electricity.

Almost all households have access to phones, but there are large differences between rural and urban areas with access to a computer (20.3 percent in urban, 5.2 percent in rural) and the internet (59.2 percent in urban, 34.0 percent in rural) (Figure 7).

Each circle represents the proportion of the specified regional population with access to the indicated information or communication technology.

Environmental Dimension

Nepal has a varied geography composed of mountains, hills, plains, and wetlands, and it is prone to natural hazards. The 2021 ND Gain index ranks Nepal low at 126 out of 182 countries, with a high vulnerability (42nd most vulnerable) and relatively low level of readiness (rank 120th most ready).23 A report by the Asian Development Bank estimates that under the “business as usual” scenario (i.e., no deviations from the fossil fuel intensive path), climate change will lead to a 2.2 percent loss of annual GDP by 2050.24

When an intermediate scenario regarding future emissions is used (RCP 4.5 where emissions are supposed to increase until 2040 and decrease after that), Nepal is expected to see an increase in the number of days above 95 degrees Fahrenheit, from (at the median probability) 23.2 days for the period 2020–2039, 27 days for the period 2040–2059, and up to 36 days for 2080–2099.25,26 Both the average winter and summer temperatures for Nepal are projected to increase over the period 2020 to 2099, with the winter average temperature increasing from 49.5 degrees for the period 2020–2039 to 52 degrees for the period 2080–2099.27 Given the large diversity of geographical regions in Nepal, not all areas will be affected similarly. Using the Coupled Model Inter-Comparison Project phase 6 (CMIP6) scenarios under two shared socioeconomic pathways (SSP245 and SSP585), the mid-hills area is expected to see increasingly higher levels of precipitation and an increasing number of extreme events that will result in a growing number of floods, landslides, and soil erosion for the near future (until 2050).28

Other areas—such as the Seti Khola catchment in the western part of the country—are projected to see a decrease in precipitation, but more than 25 percent of people living in this area will see an increasing risk of flooding and landslides due to an increased rate of snow melt and climate variability.29

However, increases in temperature (and carbon dioxide level) are expected to result in a 16 percent increase in rice production in the colder hills and mountains of Nepal by 2080.30

——————————————————————————————

1 U.S. Census Bureau, International Database (IDB), 2022, <www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/country?COUNTRY_YEAR=2022&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2022&FIPS_SINGLE=NP>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

2 World Bank, “Urban Population % of Total Population) – Nepal,” 2022, <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=NP>, accessed on 10/27/2022.

3 UN Resident Coordinator Office (UNRCO), 2017, <https://un.info.np/Net/NeoDocs/View/8225#:~:text=There%20are%20283%20municipalities%20in,metropolitan%20Cities%20and%20276%20Municipalities>, accessed on 07/30/2022.

4 U.S. Census Bureau, International Database (IDB), 2022, <www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/country?COUNTRY_YEAR=2022&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2022&FIPS_SINGLE=NP>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

5 U.S. Census Bureau, International Database (IDB), 2022, <www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/country?COUNTRY_YEAR=2022&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2022&FIPS_SINGLE=NP>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

6 World Bank, “Rural Population % of Total Population) – Nepal,” 2022, <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=NP>, accessed on 05/01/2022.

7 World Bank, “Rural Population (% of Total Population) – South Asia,” 2022, <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=8S>, accessed on 05/01/2022.

8 U.S. Census Bureau, International Database (IDB), 2022, <www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/country?COUNTRY_YEAR=2022&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2022&FIPS_SINGLE=NP>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

9 U.S. Census Bureau, International Database (IDB), 2022, <www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/country?COUNTRY_YEAR=2022&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2022&FIPS_SINGLE=NP>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

10 United Nations Development Programme, (UNDP), “Human Development Insights,” 2022, <https://hdr.undp.org/en/content/latest-human-development-index-ranking>, accessed on 10/27/2022.

11 TCdata360, “GCI4.0: Mean Years of Schooling,” World Bank, 2022, <https://tcdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/h22a4bb2b?country=NPL&indicator=41393&viz=line_chart&years=2017,2019>, retrieved on 05/23/2022.

12 Global Food Security Index 2022 report, Economist Impact, 2022, <Https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/Downloads>.

13 World Bank, “GDP per Capita, PPP (Current International $) – Nepal,” 2022, <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?locations=NP&most_recent_value_desc=false>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

14 Cosic, D., S. Dahal, and M. Kitzmuller, “Climbing Higher: Toward a Middle-Income Nepal. Country Economic Memorandum,” World Bank, Washington, DC, 2017, <https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/358501495199225866/pdf/115156-CEM-PUBLIC-SAREC-70p-Country-Economic-Memorandum-19-May-2017.pdf>, accessed on 05/19/2022.

15 World Bank, “GDP per Capita Growth, South Asia-Nepal,” 2022, <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG?locations=8S-NP>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

16 United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), “Nepal: Gorkha Earthquake 2015,” <www.preventionweb.net/collections/nepal-gorkha-earthquake-2015>, accessed on 05/19/2022.

17 Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Nepal with Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) University of Oxford, “Nepal Multidimensional Poverty Index: Analysis Towards Action,” Government of Nepal National Planning Commission, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2021, page v., “Poverty” here is measured using the multidimensional poverty index. These statistics use the new definition of urban areas as implemented by the Nepalese government.

18 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), “FAO in Nepal. Nepal at a Glance,” <www.fao.org/nepal/en/> accessed on 05/01/2022.

19 International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), World Bank, CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS),, and Local Initiatives for Biodiversity Research and Development (LI-BIRD), “Climate-Smart Agriculture in Nepal. CSA Country Profiles for Asia Series,” CIAT, The World Bank, CCAFS, LI-BIRD, Washington, DC, page 26.

20 World Bank, “Personal Remittances, Received (Percent of GDP) - Nepal,” 2022, <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=NP>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

21 CIAT, World Bank, CCAFS, and LI-BIRD, “Climate-Smart Agriculture in Nepal. CSA Country Profiles for Asia Series,” International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), The World Bank, CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), Local Initiatives for Biodiversity Research and Development (LI-BIRD), Washington, D.C., page 26.

22 Government of Nepal National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF Nepal, “Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019,” 2020, page 426, <www.unicef.org/nepal/reports/multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-final-report-2019>, accessed on 11/09/2022.

23 University of Notre Dame, “ND-GAIN Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative,” 2022, <https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/>, accessed on 05/01/2022. ND-GAIN index ranks countries based on their vulnerability to climate change and readiness to deal with these vulnerabilities.

24 Ahmed, M., and S. Suphachalasai, “Assessing the Costs of Climate Change and Adaptation in South Asia, ”Asian Development Bank, 2014, <www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/42811/assessing-costs-climate-change-and-adaptation-southasia.pdf>, accessed on 05/01/2022.

25 Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) are projections of radiative forcing components that are meant to serve as input for climate modeling, pattern scaling and atmospheric chemistry modeling. The RCP 4.5 scenario is a stabilization scenario, meaning that the radiative forcing level stabilizes at 4.5 W/m2 before 2100, <https://sos.noaa.gov/catalog/datasets/climate-model-temperature-change-rcp-45-2006-2100/>.

26 Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC), “Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report Fifth Assessment Report. Future Changes,” 2014, <https://ar5-syr.ipcc.ch/topic_futurechanges.php>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

27 Climate Impact Lab, <https://impactlab.org/map/#usmeas=absolute&usyear=1981-2010&gmeas=absolute&gyear=1986-2005&tab=global>, accessed on 11/09/2022.

28 Chhetri, R., et al., “How Do CMIP6 Models Project Changes in Precipitation Extremes Over Seasons and Locations Across the Mid Hills of Nepal?,” Theoretical Applied Climatology, 145, 2021, pp. 1127–1144, <https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-021-03698-7 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00704-021-03698-7>, accessed on 05/30/2022.

29 Heyojoo, B. P., Yadav, N. K., Subedi, R., “Assessments of Climate Change Indicators, Climate-Induced Disasters, and Community Adaptation Strategies: A Case From High Mountain of Nepal,” In: Li, A., Deng, W., Zhao, W. (eds) “Land Cover Change and Its Eco-Environmental Responses in Nepal,” Springer Geography, Springer, Singapore, 2017, <https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2890-8_9>, accessed on 03/05/2022.

30 Ahmed, M., and S. Suphachalasai, “Assessing the Costs of Climate Change and Adaptation in South Asia, ”Asian Development Bank, 2014, <www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/42811/assessing-costs-climate-change-and-adaptation-southasia>, accessed on 05/01/2022.