Census Protections Evolve Continuously to Address Emerging Threats

When U.S. Marshals conducted America’s first census in 1790, they posted the answers in the town square so locals could check for accuracy, as required by law. This practice continued until 1850.

How times have changed. Today, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) may release decennial census records after 72 years. The most recent census available to the public is the 1940 Census.

The privacy law, in Title 13 of the United States Code, mandates that information about specific individuals, households and businesses is not revealed, even indirectly through our published statistics.

The U.S. Census Bureau and its employees must protect respondent privacy and confidentiality at every stage of the data lifecycle, from collection through processing, publication and storage.

The privacy law, in Title 13 of the United States Code, mandates that information about specific individuals, households and businesses is not revealed, even indirectly through our published statistics.

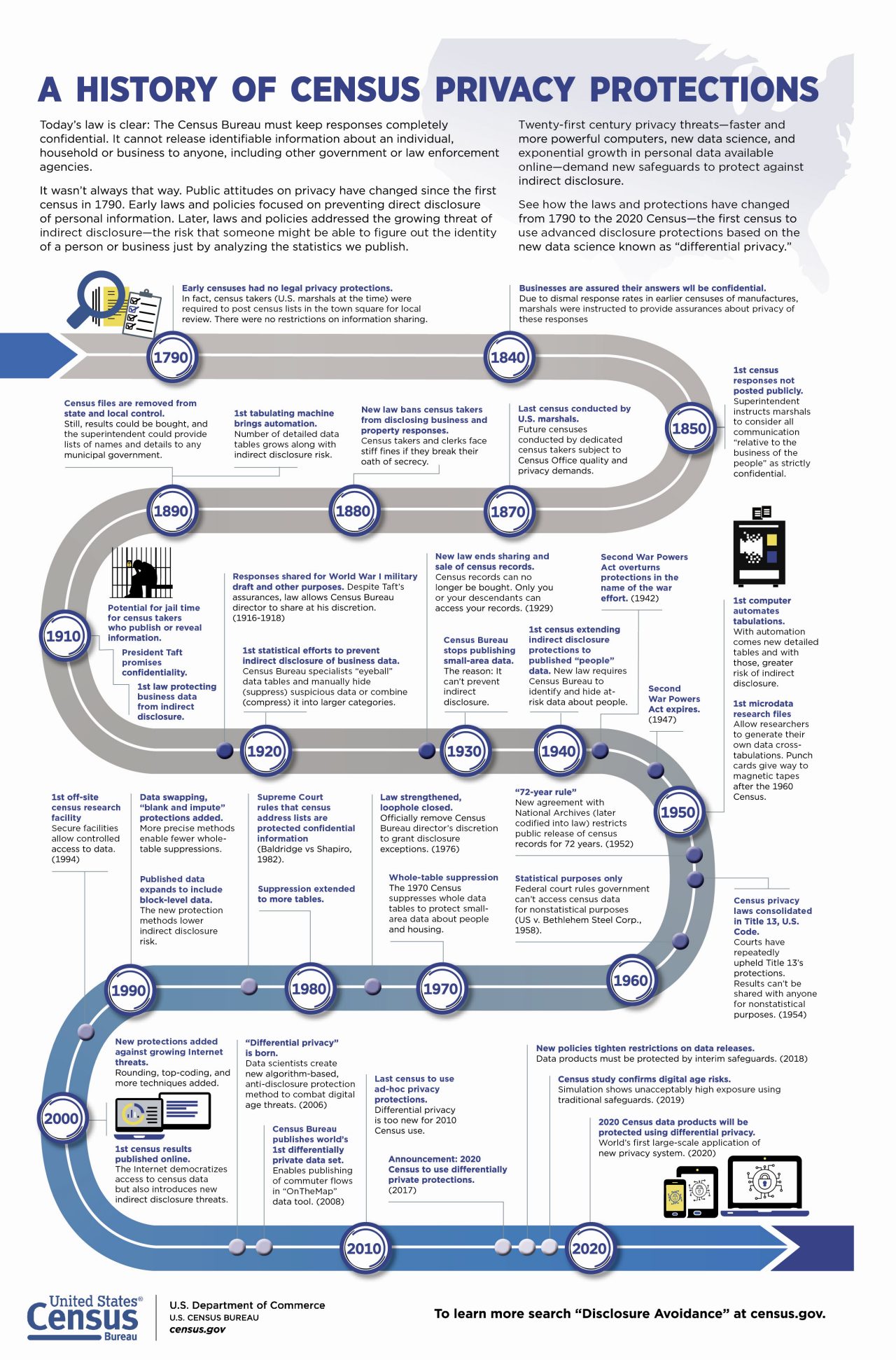

A new Census Bureau infographic below charts the path of census safeguards from 1790 to now, from zero privacy to today’s absolute strictures designed to maintain public trust.

The 1800s

The earliest steps to protect the data addressed the most basic privacy challenges – but for businesses only.

Amid fears that competitors could extract sensitive information from the data, participation in the 1820 Census of Manufactures was so low that Congress decided not to collect the data in 1830. Realizing how important this information was, officials in 1840 provided assurances to businesses that their information would be safe.

In 1880, a new law gave those assurances teeth by adding stiff fines for census workers who violated that privacy. A separate law in 1910 added potential jail time.

Those earlier laws addressed direct disclosure of business information.

The 1900s

The first law to address indirect disclosure wasn’t enacted until 1910. That law made it incumbent upon the Census Bureau to ensure that census statistics couldn’t be reverse-engineered to reveal business identities.

The Census Bureau used a combination of techniques to comply. In 1930, it stopped publishing small area data altogether because, at the time, there was no way to disguise identities at that level.

In 1940, the indirect disclosure law was officially extended from businesses to data about people, as well.

The 1950s ushered in the age of computers and with it the ability to tabulate and publish more data for more levels of geography than ever before. But the proliferation of data brought with it greater indirect disclosure risks.

In 1970, the Census Bureau again suppressed (stopped publishing) whole tables for small areas and groups deemed too at risk.

In the decades that followed, staff worked to limit table suppression by adding more layers of statistical “noise” by swapping characteristics, “topcoding” values to limit outliers, rounding numbers and using other methods that affected precision but better protected privacy.

These “traditional” statistical disclosure methods worked well for decades. But new threats — the rise of the internet, exponentially faster computing, new data science and an abundance of personal data readily available online —rendered those methods ineffective.

The 2000s

The 2020 Census will be the first census to use a powerful new privacy protection system designed for the digital age. It uses a rigorous mathematical process, drawing from cryptography, to guarantee a level of privacy regardless of any new technology the future brings.

We’ve come a long way from those early days of posting local responses in the town square. Visit our Statistical Safeguards pages to learn more.

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.

-

America Counts StoryU.S. Census Bureau Unveils 2020 Census Advertising CampaignJanuary 14, 2020Today in Washington, D.C., members of Congress, federal agency leaders, partners and media get a preview of the $500 million Integrated Communications Campaign.

-

America Counts Story2020 Census Count Guides Funding of New Roads and BridgesDecember 04, 2019Billions of dollars in federal funds are spent annually on critical transportation services. The 2020 Census may help decide...

-

America Counts Story2020 Census Recruitment Campaign Kicks Off TodayOctober 22, 2019The Census Bureau needs to hire about 500,000 census takers across the country in 2020. Peak recruiting efforts start now.

-

IncomeHow Income Varies by Race and GeographyJanuary 29, 2026Median income of non-Hispanic White households declined in five states over the past 15 years: Alaska, Connecticut, Louisiana, Nevada, and New Mexico.

-

HousingRental Costs Up, Mortgages Stayed FlatJanuary 29, 2026Newly Released American Community Survey compares 2020-2024 and 2015-2019 housing costs by county.

-

HousingShare of Owner-Occupied, Mortgage-Free Homes Up in 2024January 29, 2026The share of U.S. homeowners without a mortgage was higher in 2024 than a decade earlier nationwide and in every state, though not all counties saw increases.

-

PopulationU.S. Population Growth Slowest Since COVID-19 PandemicJanuary 27, 2026The decline in international migration was felt across the states, though its impact varied.