Children Working at the Same Employer as Their Parents Saw Persistent Increases in Earnings

Parents help their children with many things, but to what extent do they help them find a job?

Working for a parent’s employer leads to a 24% increase in earnings at a young worker’s first job compared to those hired without a parental connection. Three years later, individuals who began their careers where their parents work earned 20% more than their peers who did not.

A job with a parent’s employer can pay off and the advantage grows with the parent’s earnings.

Matthew Staiger, a Harvard Opportunity Insights researcher, used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics program and 2000 Decennial Census to reveal how workers can benefit from their parents’ employment connections.

The Census Bureau and Harvard University have collaborated through Harvard’s Opportunity Insights, which uses Census Bureau data to study economic mobility including the creation of the Opportunity Atlas.

Staiger presented his research at a Census Bureau webinar in August, 2024. He used the data to create a sample of 48 million people who lived with a parent, graduated high school between 2000 and 2013, and resided in a state that reported LEHD data at least two years prior to their graduation.

Among his findings: parents’ employment connections can help their children earn higher wages throughout their careers whether the parents run the company or simply work there.

“Intergenerational persistence in earnings is attributable, in part, to parents using their connections to provide access to higher paying firms,” Staiger said in the webinar. “Social networks, more broadly defined, could actually be quite an important determinant of intergenerational mobility.”

Working With Mom or Pop

In the United States, it is not uncommon for individuals to find jobs through their parental connections. Five percent of people in the sample got their first job at the same firm where a parent was employed. By age 30, 29% of sampled individuals had done so.

A job with a parent’s employer can pay off and the advantage grows with the parent’s earnings. Children of parents in the top 40% of earners experienced gains more than two times greater than those with parents in the bottom 40%.

The increase in earnings largely stemmed from parents providing access to higher paying blue-collar jobs for their children who otherwise likely would have worked in the “unskilled” service sector (Figure 1).

Parents provided access to firms that paid higher wages rather than to high-paying jobs within those firms, proving the proverb, “it’s all about who you know.”

The Wages of Kin

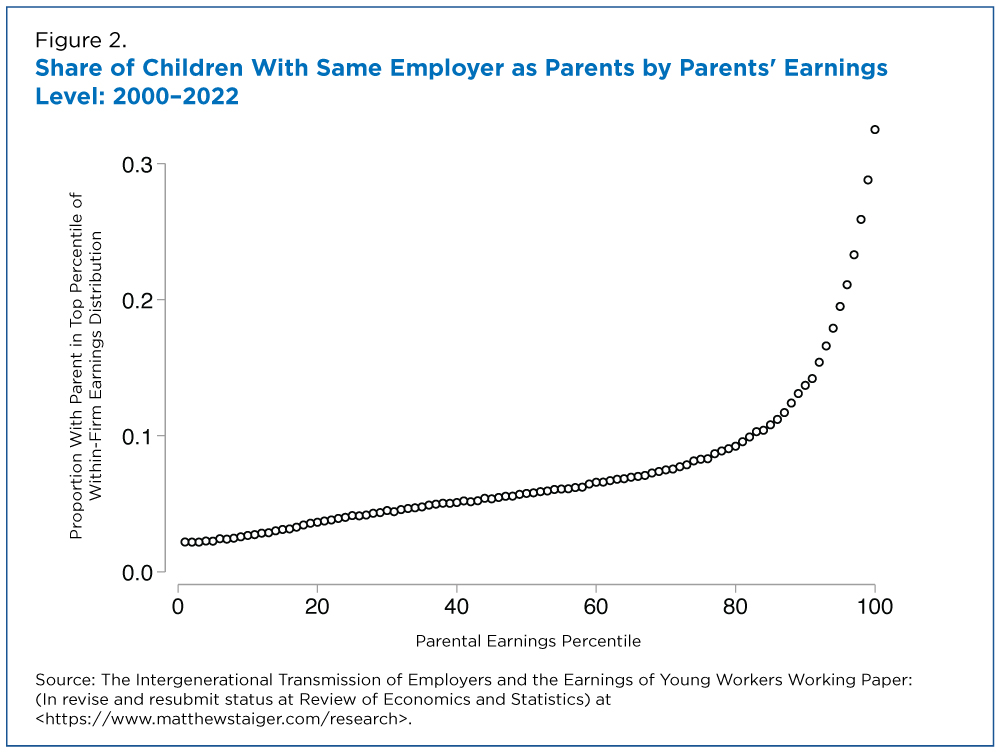

The more a parent earned, the more likely their children were to work for the same employer.

Nearly a third (31%) of individuals whose parents were in the top 10% of earners worked for a parent’s employer at some point between ages 16 and 30, compared to 25% in the bottom 10% of earners.

But can only “big wigs” land jobs for their kids?

Of sampled individuals who worked for a parent’s employer, only 19% had a parent in the top 1% of earners within their firm, suggesting that many of these parents were themselves employees rather than owners or top executives.

Equal Opportunity?

Although most parents who worked for the same employer as their kids were not top earners, those who were helped their children most. Children of top earners were more likely to get a job with their parent’s employer and experience larger earnings gains than peers in the sample who did not.

One explanation is that higher-earning parents are more likely to hold positions of authority at their firms.

The relationship between the probability of working for a parent’s employer and parental earnings tracked closely to the probability that the parents were among their firm’s top earners (Figure 2).

Intergenerational Benefit

Access to a parent’s employer can shape early-career outcomes and intergenerational mobility.

“The headline finding … is that these connections explain a modest, but not insignificant, share of the correlation between the income of parents and children,” Staiger said. “However, parents may be able to provide access to jobs outside of their own place of work” through extended family, friends, or co-workers.

This raises the possibility that parental connections play an important role in shaping economic opportunity.

Even workers recently laid off benefited from parental employment connections: Those who joined their parent’s employer got access to higher-paying firms and earned 23% more after being displaced than those who found jobs without a parental connection.

Education played a role as well. Children without a college degree were twice as likely as their college-educated siblings to work for their parents’ employer.

Staiger’s research suggests parental employment connections may be a key driver of socioeconomic mobility, particularly since many jobseekers find employment through social contacts.

“These connections appear to benefit white males from high-income families the most,” Staiger said.

The bottom line: Understanding the parent-employment connection might help workers navigate the labor market more successfully.

Related Statistics

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.

-

Business and EconomyMore Women in Manufacturing Jobs in Every Age GroupOctober 03, 2022In the runup to Manufacturing Day on Oct. 7, we look at the growing role of women in manufacturing.

-

VeteransWhat Are Veterans’ Job Prospects After They Serve?January 14, 2025New U.S. Census Bureau data show how veterans fare when they transition to the civilian labor force.

-

EmploymentDo Young Workers Still Have Summer Jobs?July 06, 2022As the school year ends, the prospect of summer jobs for youths rises but there’s been a declining overall trend in young people working during summer months.

-

EmploymentUnexpected Workforce Trends in Post-Pandemic ManhattanFebruary 19, 2026Recent jobs data show Manhattan’s workforce shares have shifted younger, more female and into the Accommodation and Food Services industries after the pandemic.

-

Business and EconomyAbility to Borrow Money Offers Clues to Financial Health of BusinessesFebruary 10, 2026Most employer businesses that applied for credit got what they asked for, according to the latest available data from the Annual Business Survey.

-

HousingShare of Owner-Occupied, Mortgage-Free Homes Up in 2024January 29, 2026The share of U.S. homeowners without a mortgage was higher in 2024 than a decade earlier nationwide and in every state, though not all counties saw increases.

-

HousingRental Costs Up, Mortgages Stayed FlatJanuary 29, 2026Newly Released American Community Survey compares 2020-2024 and 2015-2019 housing costs by county.