Tribally Owned Casinos May Improve Economic Conditions on Reservations and Lower Unemployment for Nearby People of All Races

American Indians on tribal lands in the United States have historically faced some of the nation’s worst economic conditions.

The proportion of American Indian people living below the poverty line in 1989 was 31%, considerably higher than the 13% national poverty rate at the time.

The expansion of tribal casinos that began in the 1990s helped improve economic conditions faster for American Indians relative to the U.S. population as a whole, according to joint U.S. Census Bureau and university research, though there is still progress to be made: the American Indian poverty rate was 19.6% in 2024, greater than that year’s national average of 12.1%, according to Census Bureau data.

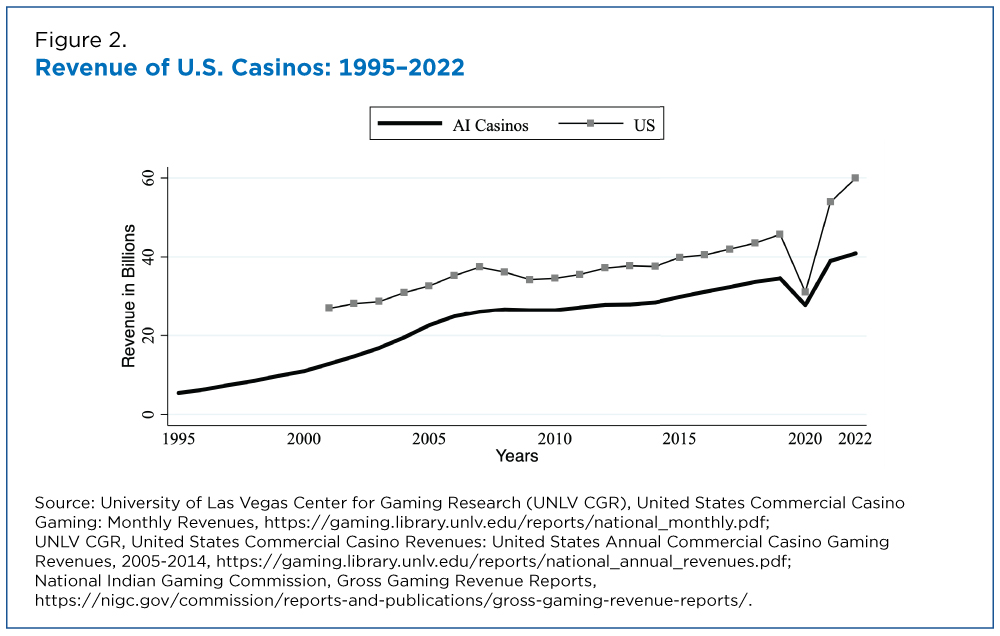

In recent years, the American Indian gaming industry generated more than $40 billion annually.

A working paper, written by Maggie R. Jones (Census Bureau), Randall Akee (Census Bureau and University of California Los Angeles) and Emilia Simeonova (Johns Hopkins University) used census data to evaluate the ZIP-code-level economic impact of tribal casinos on nearby people and places.

Casino Economy

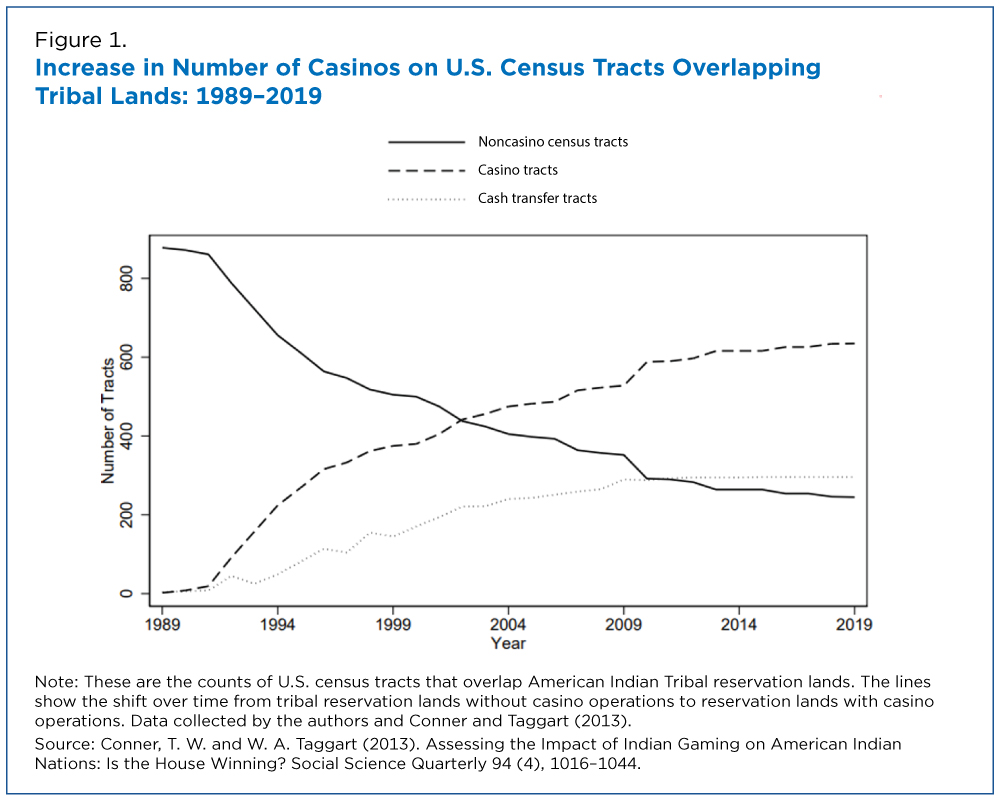

After Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) in 1988, the number of U.S. census tracts with an American Indian tribal casino operation surged from near zero in 1989 to nearly 600 by 2019 (Figure 1).

The research shows that tribal casino operations boost wages for American Indians and reduce unemployment for nearby people of all races employed in casino-related industries (Accommodation, Food Service and Arts and Entertainment) when compared with non-casino reservation ZIP codes in the same state.

It also indicates that direct cash transfer programs (i.e., per capita payments of casino profits) may have contributed to improved living standards, on average, for tribal citizens living on reservations.

Sovereignty and Solvency

In recent years, the American Indian gaming industry generated more than $40 billion annually (Figure 2).

How do American Indian tribes “split the pot”?

Under the IGRA, tribe-owned casino revenue must support tribal economic development and welfare, including local charities and, in some cases, sharing it with state and local governments.

This means the IGRA, by permitting casino operations, can be viewed as a “place-based” policy that targets specific geographies for economic development.

The law not only re-affirmed tribal nation’s sovereign right to form government-owned enterprises — it enabled the large-scale tribal gaming industry as it exists today.

Prior to 1988, tribal gaming was limited to small-scale bingo and card games on reservations in California and Florida. High-stakes casinos only existed in Nevada and New Jersey.

Tribal casino operations, post-IGRA, created a revenue stream almost exclusive to reservation lands in much of the United States.

The Benefits of Casino Ownership

Economic conditions for American Indians living on reservations improved significantly as the tribal casino industry took off in the first two decades of the IGRA, according to the research.

During this time, American Indians living on reservation lands (regardless of the presence of a casino or cash transfer program) saw a 46.5% rise in real per capita income compared to 7.8% for the United States as a whole.

Casino revenues helped tribes develop their economic base through investments in infrastructure and expanded employment. Additionally, some tribal nations provided their citizens with unconditional cash transfers (from casino profits) designed to improve tribal development and welfare.

Citizens of casino-owning tribal nations received a significant cash infusion when their government adopted cash-transfer policies. Provided that the tribal nation has opted for unconditional cash transfers, all tribal citizens are eligible to receive the transfers, regardless of whether they live on a reservation.

These programs are among the earliest and longest running examples of universal basic income in the United States.

But added income wasn’t the only benefit, according to the study.

In the first two decades after IGRA’s passage American Indians living on reservations experienced:

- About an 11% decrease in childhood poverty compared to no significant change for the country as a whole.

- A roughly 7% increase in labor force participation by American Indian women, compared to 3% for the country as a whole.

- A 4% reduction in overall unemployment compared to no significant change for the country as a whole.

To access this and other working papers, visit the Census Working Papers website. Working papers are intended to make Census Bureau research accessible and have not undergone the standard review and editorial process of other Census Bureau publications.

Related Statistics

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.

-

PopulationHow Native North American Language Use Changed in the United StatesJune 03, 2025An updated table package reveals how over 500 languages spoken at home changed from 2013 to 2021.

-

PopulationImproving Access to Funding for Indigenous CommunitiesJanuary 12, 2024The Opportunity Project and U.S. Economic Development Administration partner to improve access to capital for American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

-

American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN)Detailed Data for Hundreds of American Indian and Alaska Native TribesOctober 03, 20232020 Census detailed data available for close to 1,200 AIAN tribes and villages for the nation, states and tribal areas.

-

IncomeHow Income Varies by Race and GeographyJanuary 29, 2026Median income of non-Hispanic White households declined in five states over the past 15 years: Alaska, Connecticut, Louisiana, Nevada, and New Mexico.

-

HousingRental Costs Up, Mortgages Stayed FlatJanuary 29, 2026Newly Released American Community Survey compares 2020-2024 and 2015-2019 housing costs by county.

-

HousingShare of Owner-Occupied, Mortgage-Free Homes Up in 2024January 29, 2026The share of U.S. homeowners without a mortgage was higher in 2024 than a decade earlier nationwide and in every state, though not all counties saw increases.

-

PopulationU.S. Population Growth Slowest Since COVID-19 PandemicJanuary 27, 2026The decline in international migration was felt across the states, though its impact varied.