Global Population Estimates Vary but Trends Are Clear: Population Growth Is Slowing

Using data from the International Database, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates the world population hit 8 billion on September 26.

Emphasis on the word estimates.

There are many sources of uncertainty in estimating the global population, and it’s unlikely this population milestone was reached on that exact date.

For example, the United Nations (U.N.) Population Division estimates the world population reached 8 billion on November 15, 2022.

Only around 4% of the world population (all in Africa) lives in a country with very high fertility — above 5 children per woman. Even in countries with very high fertility, fertility is generally lower than it was in the past.

Why the discrepancy? Many of the world’s most populous countries (such as India and Nigeria), haven’t conducted a census in over 10 years, and many countries lack civil registration and vital statistics systems that accurately record births and deaths among their population.

Given the lack of precise population data worldwide, the U.N. and Census Bureau estimates are not that far apart, and both imply similar overall trends.

Population Growing at Slower Pace

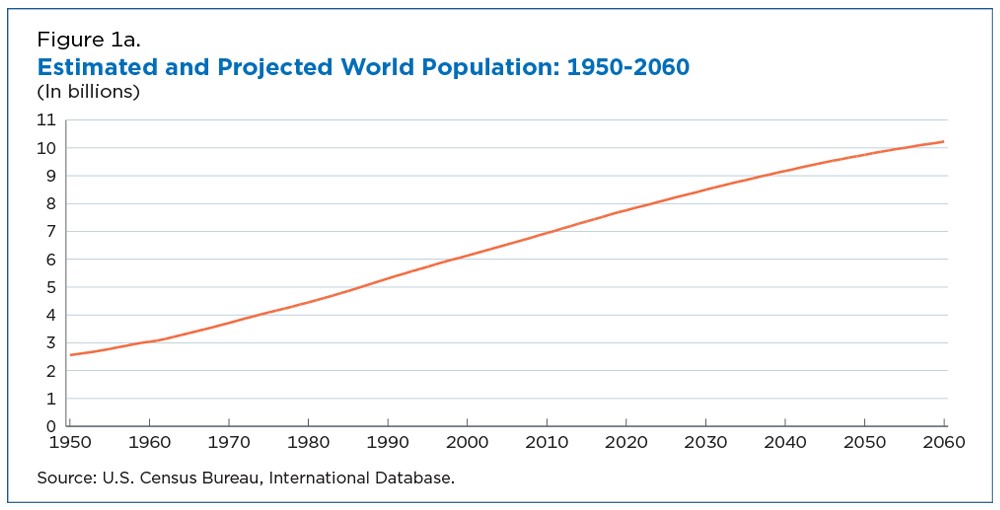

The rate of growth peaked decades ago in the 1960s and has been declining since and is projected to continue declining.

While it took 12.5 years for the world to go from 7 billion to 8 billion people, we project it will likely take 14.1 years to go from 8 billion to 9 billion, and another 16.4 years to go from 9 billion to 10 billion.

Despite a slowdown, we project the world population will reach 10.2 billion by 2060.

These broad global trends mask wide diversity. Population growth is the result of fertility, mortality, migration and the share of the population at certain ages. These trends all differ from country to country and, as a result, population growth varies around the world.

Declining Fertility Continues

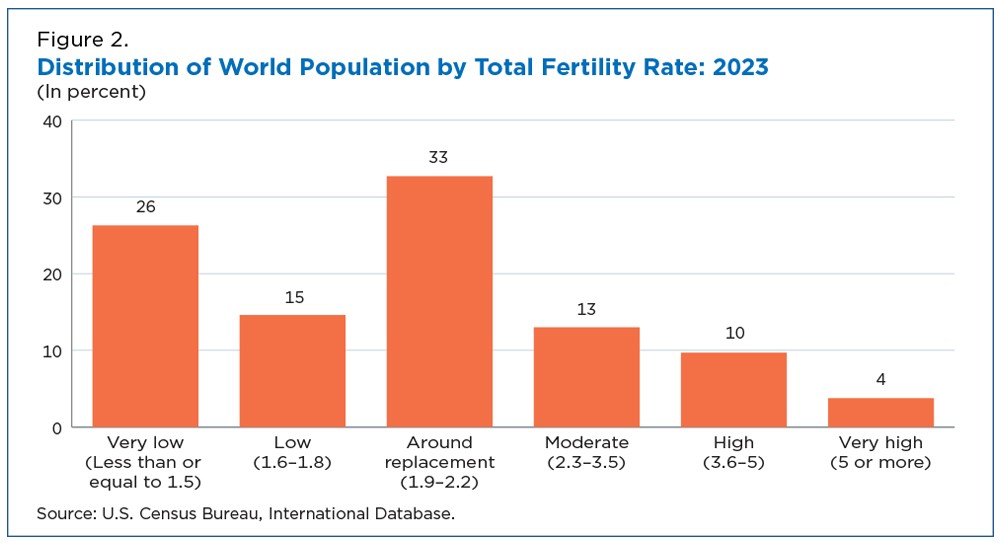

Nearly three quarters (74%) of the earth’s population reside in countries where fertility is around or below the replacement level.

It is widely believed that 2.1 is the replacement-level fertility rate — the number of births a woman would need to have in her lifetime to replace herself and the father. However, the precise level of fertility necessary for long-term replacement varies between countries due to different mortality rates.

Around 33% of the world population — approximately 1 in 3 people — lives in a country with a fertility rate close to replacement, including diverse countries such as India, Tunisia and Argentina.

Demographers once assumed fertility would stop declining once it reached replacement levels. But it has continued to decline below replacement levels in many countries.

Around 15% of the world’s population lives in a country with low fertility of 1.6 to 1.8 children per woman. This includes a diverse range of countries like Brazil, Mexico, the United States and Sweden.

Another 26% — about 1 in 4 people — lives in a country with very low fertility at 1.5 children or fewer per woman. Such countries include China, South Korea and Spain.

Another 23% lives in a country with moderately high fertility between 2.3 and 5.0 children. This broad category includes a diverse range of countries like Papua New Guinea, Israel and Ethiopia.

Only around 4% of the world population (all in Africa) lives in a country with very high fertility — above 5 children per woman. Even in countries with very high fertility, fertility is generally lower than it was in the past.

And we project that by 2060, no country will have an average of four or more children per woman, let alone five or six children per woman.

It’s projected that Benin will have the world’s highest projected total fertility rate (3.8) in 2060. There will, of course, still be women who have four or more children, but it is unlikely entire countries will average four or more children per woman.

Most Growth Will Come From Adult Populations

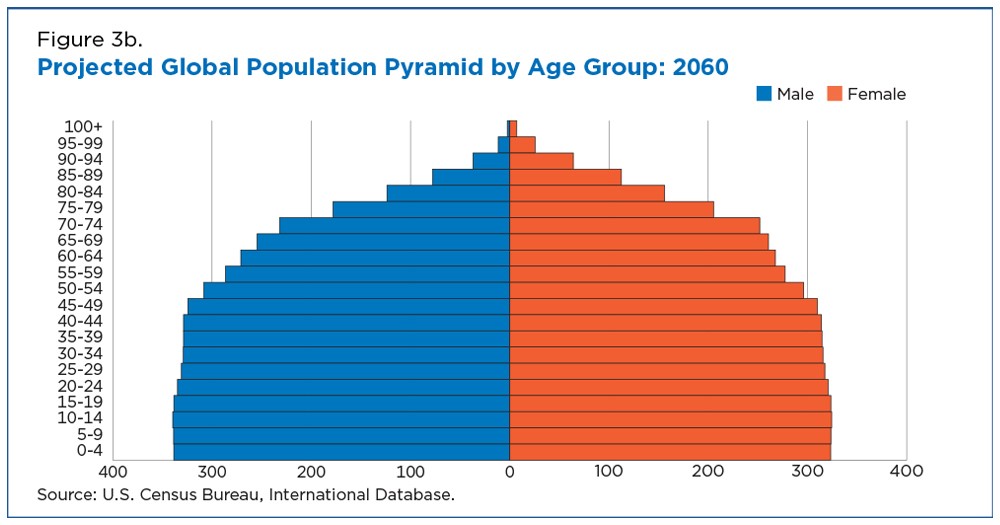

The world population is projected to keep growing despite declining fertility rates. In fact, we estimate the number of infants already peaked in 2017. Instead, population growth in the future will come from larger groups of people at adult ages. Demographers call this phenomenon population momentum.

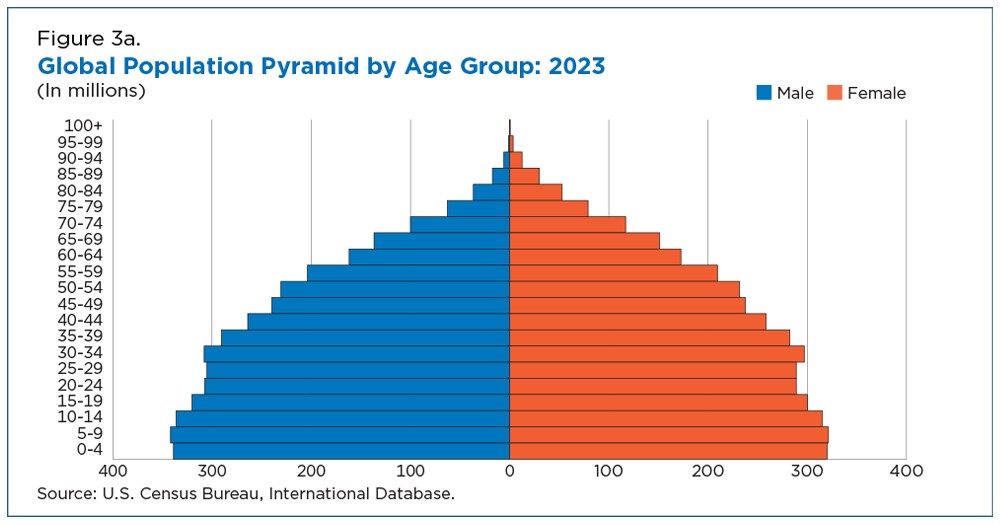

Figure 3 shows the world population by age in 2023 and the projected population by age in 2060. Population growth between now and 2060 will be from the population pyramid “filling up” previously sparse older age groups, not from growing numbers of births.

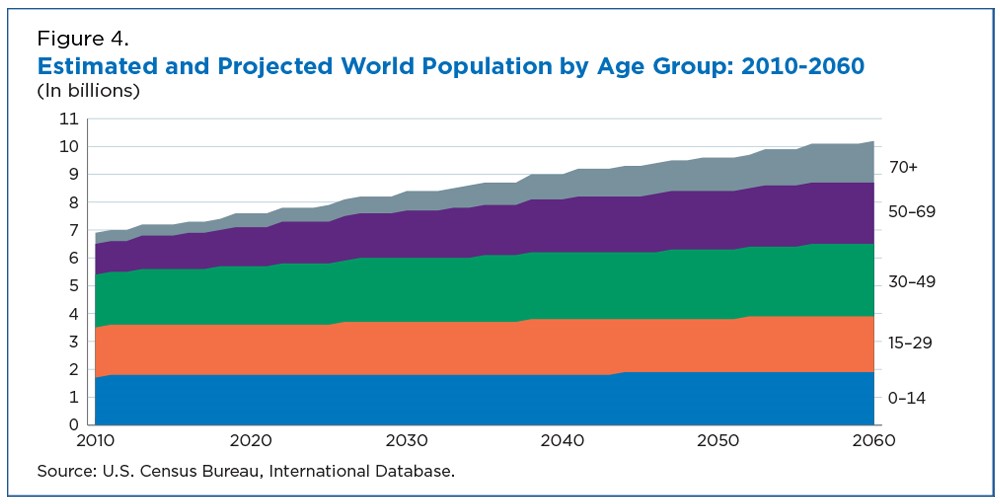

Figure 4 shows how the growth of the older-adult population is projected to make up most of the population growth between now and 2060. Future population growth will be coincident with population aging.

Global Aging

As fertility declines, there are proportionally fewer younger people and more older people.

The share of the population at young ages has been declining. Today, 32% of people are 19 or younger. By 2060, that number is projected to slip to 26%.

As the share of young people declines, the proportion of people at older ages increases. Today, 10% of the world is 65 or older and their share is projected to double to 20% by 2060.

As a result, the median age is changing. Today, the global median age is 32 (half the population is younger and half older). By 2060, however, the global median age is projected to climb to 39 years.

These general trends vary by country. Niger is the world’s youngest country, with a median age of 15 in 2023. Monaco, by contrast, is the oldest, with a median age of 56 in 2023.

Increasing Life Expectancy

In many countries where young-age mortality is already low, gains in life expectancy come from improving conditions at older ages.

Canada, for instance, did not experience big declines in young-age mortality between 2000 and 2023, but its total life expectancy increased by an average of about 4 years, largely from reduced mortality at older ages.

For many other countries, however, life expectancy trends are driven more by dramatic declines in child mortality. In Niger, for example, child mortality declined from around 224 deaths of children under 5 per 1,000 births in 2000 to 103 deaths per 1,000 births in 2023.

As a result, the country’s average life expectancy at birth increased from 45 years in 2000 to 60 years in 2023. We project that Niger will continue this trend and that child mortality will drop to 45 deaths per 1,000 births by 2060.

Life expectancy gains from reducing mortality at young ages make populations younger. As fewer children die, there are more children in the population.

While life expectancy is generally increasing, there are some exceptions. Many countries saw a decline in life expectancy due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We are gradually incorporating COVID-19 mortality into the population estimates available in the International Database (IDB) as more recent mortality data become available.

Related Statistics

-

Stats for StoriesWorld Population Day: July 11, 2025The U.S. Census Bureau’s International Database projects that the world population will reach 8.1 billion in 2025 and 9 billion in 2038.

-

Stats for StoriesNew Year's Day 2025: January 1, 2025The U.S. Census Bureau projects the U.S. population will be 341,145,670 on Jan. 1 – 2,640,171 or 0.78% more than on New Year’s Day 2024.

Subscribe

Our email newsletter is sent out on the day we publish a story. Get an alert directly in your inbox to read, share and blog about our newest stories.

Contact our Public Information Office for media inquiries or interviews.

-

PopulationFertility Rates: Declined for Younger Women, Increased for Older WomenApril 06, 2022Despite broader stability in fertility trends, a Census Bureau analysis shows that the age at which U.S. women gave birth changed from 1990 to 2019.

-

PopulationU.S. Births Declined During the PandemicSeptember 21, 2021Several factors affect the birth rate but the pandemic did have an impact: births declined but began to rise again in March of this year.

-

PopulationDeaths Outnumbered Births in Half of All States Between 2020 and 2021March 24, 2022Higher deaths and lower fertility during the COVID-19 pandemic led to natural decrease in nearly three-quarters of the nation’s counties.

-

IncomeHow Income Varies by Race and GeographyJanuary 29, 2026Median income of non-Hispanic White households declined in five states over the past 15 years: Alaska, Connecticut, Louisiana, Nevada, and New Mexico.

-

HousingRental Costs Up, Mortgages Stayed FlatJanuary 29, 2026Newly Released American Community Survey compares 2020-2024 and 2015-2019 housing costs by county.

-

HousingShare of Owner-Occupied, Mortgage-Free Homes Up in 2024January 29, 2026The share of U.S. homeowners without a mortgage was higher in 2024 than a decade earlier nationwide and in every state, though not all counties saw increases.

-

PopulationU.S. Population Growth Slowest Since COVID-19 PandemicJanuary 27, 2026The decline in international migration was felt across the states, though its impact varied.